'Like a mole groping in the dark'

Coal miners of Northumberland and Durham

Hello, everyone. I hope that like me you’ve enjoyed some sunshine over the Easter weekend. Today it started to rain, so I’ve been putting the finishing touches to this first post in a new series about my coal miner ancestors. I have a cousin on my mother’s side who wants to know why I never write about her family. The simple answer is that I’ve inherited much less information about them. The more complex and sensitive reason is that I was never close to my mother, something that I now regret, so I don’t have the same motivation. But perhaps one way of dealing with the regret is to start writing.

Coal has been in the news recently, as the UK government took urgent measures to ensure that a shipment from Australia reached the British Steel plant in Scunthorpe in time to keep the furnaces burning. We British, of course, no longer mine our own coal, although it’s still there - in western Durham it’s said that people can dig it up in their back gardens if they want to. The phasing out of fossil fuels is good for the planet but a sad end to a proud tradition that generations of my family were associated with.

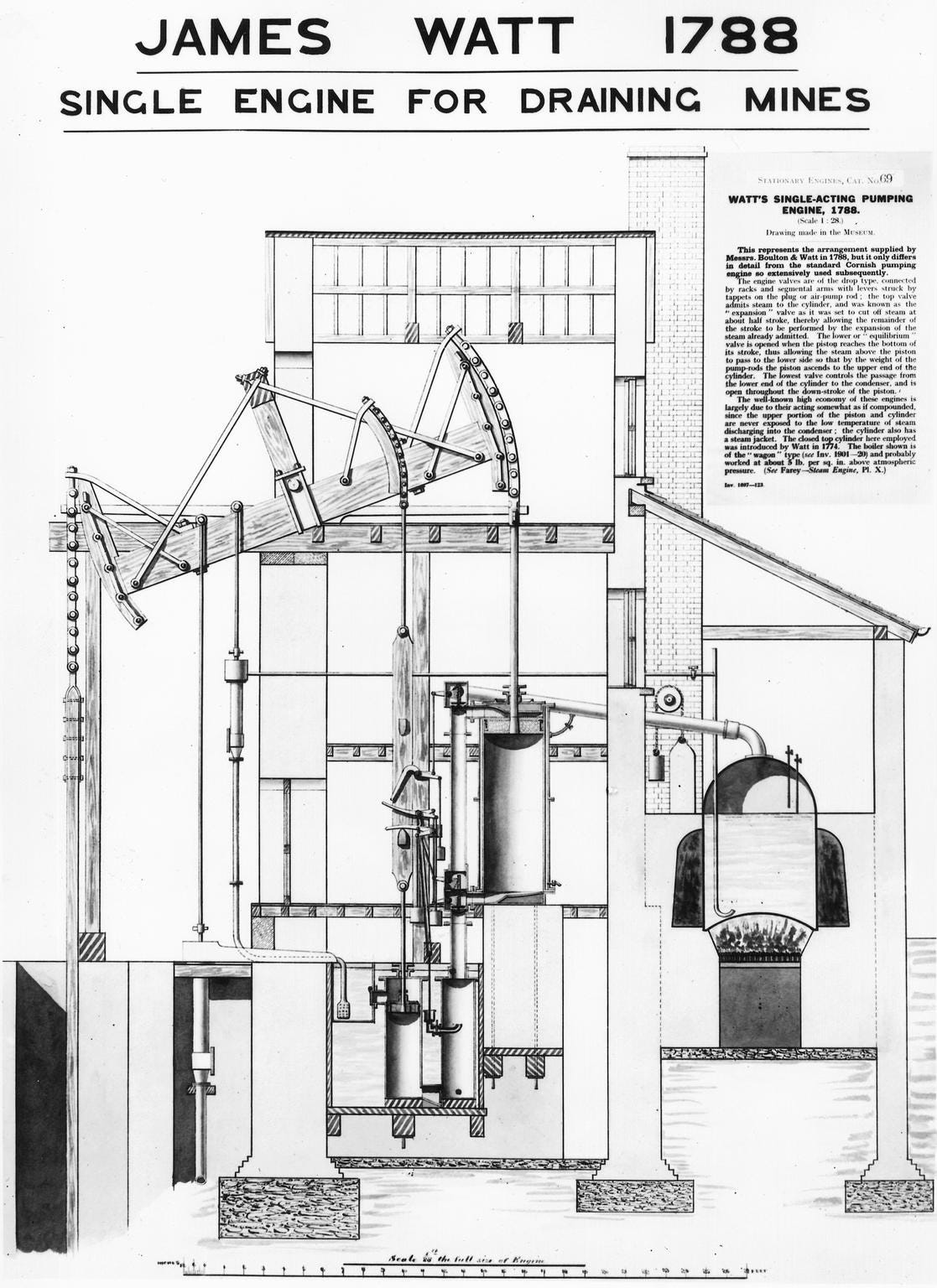

I first became fascinated by Britain’s Industrial Revolution when I researched the engineering heritage of my father’s Cornish grandmother, who came from Hayle, a town that was home to the biggest iron foundry in the world. But my interest in the revolution brought about by steam power didn’t extend to the coal that was needed to produce steam. I realise now that it should have done. George Orwell, in The Road to Wigan Pier, called coal the basis of British civilisation. The miner, he wrote, was ‘a sort of caryatid upon whose shoulders nearly everything that is not grimy is supported’. It was a symbiotic relationship: steam drove the engines that drained water from the mines, and coal was essential to make steam. Throughout the nineteenth century, the number of mines increased as engines transformed manufacturing and transport. Looms and spinning wheels disappeared from cottages and were reinvented as dangerous, noisy machines in factories, while the white sails of the great clipper ships became a rare sight as churning screws and black smoking funnels took their place.

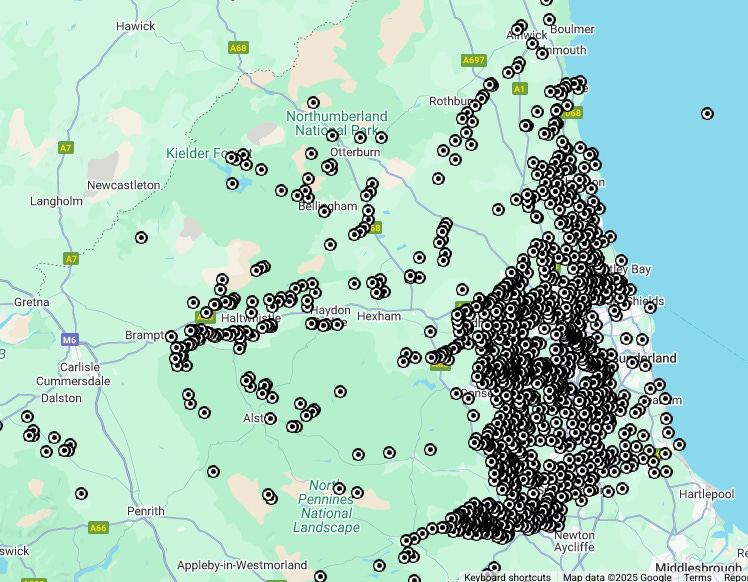

A map of the coalfields of the north east shows a forest of black pins, each one marking a spot where someone decided it was worth sinking a shaft to see what they could extract.

Of my four great-grandfathers, three were called George. I’ve written in my books about the two on my father’s side: George Smythe was a gardener’s boy from Aberdeenshire, who rose up in the world to become a respected hotel keeper, farmer, and county councillor; George Baxter was a fatherless cordwainer’s apprentice who ended up as a master tailor with a valuable property portfolio in west London. Both of them as children experienced extreme hardship, but their own sons and daughters grew up in middle class comfort. I’ve never before written about George Makepeace, father of my mother’s mother Ethel Makepeace, who lived and died a coal miner.

A further consequence of the boom in coal production was the mass movement of people. Coal had been mined in the north east since at least the sixteenth century, and in 1800 there were about 13,000 miners in Northumberland and Durham. By the end of the century this number had grown tenfold to around 135,000, and the total population of County Durham had increased from 150,000 to 1.88 million. By 1911, almost one in three of the working population were miners and the north east was producing 21% of Britain’s coal. Workers and their families arrived from Ireland, and from the other mining areas of England, as far afield as Cornwall and Devon.1 They also travelled within the north east.

George Valentine Makepeace was born in Trimdon, County Durham, in 1862, the eighth child of William and Martha Makepeace. Tracing the family back, I discovered that three generations previously, the first William Makepeace had lived in Hexham, a small market town in rural Northumberland close to Hadrian’s Wall. His son, another William, moved forty miles south to the mining area of Houghton le Spring. The move from farm to pit was one made by many men, as new mines opened up to exploit the rich coal seam that lay beneath the agricultural land of Northumberland and Durham. The profits, of course, went to the landowners in royalties. Gradually the fields were covered with houses where families like my ancestors lived. I love old maps and I’ve spent many happy hours playing with the ones available online at the National Library of Scotland, exploring how the landscape has changed over time. Here are a couple of examples covering the Trimdon area.

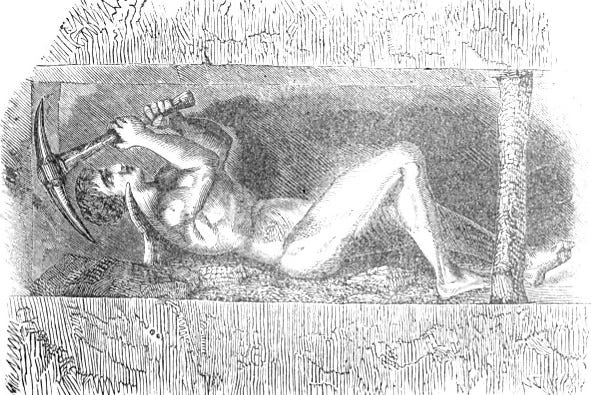

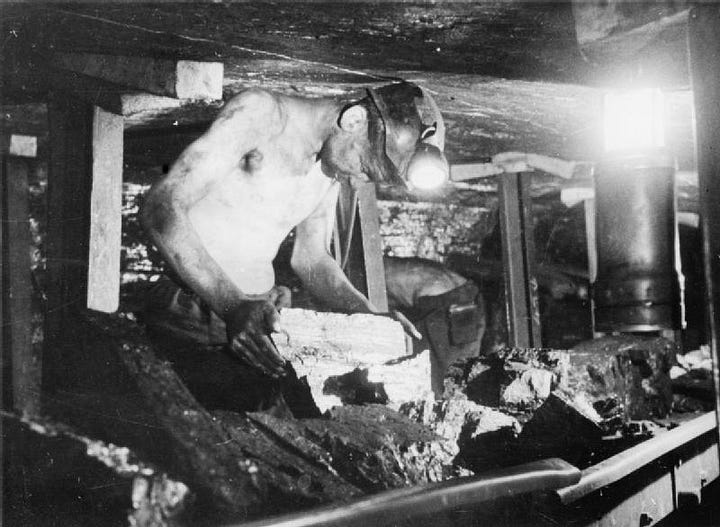

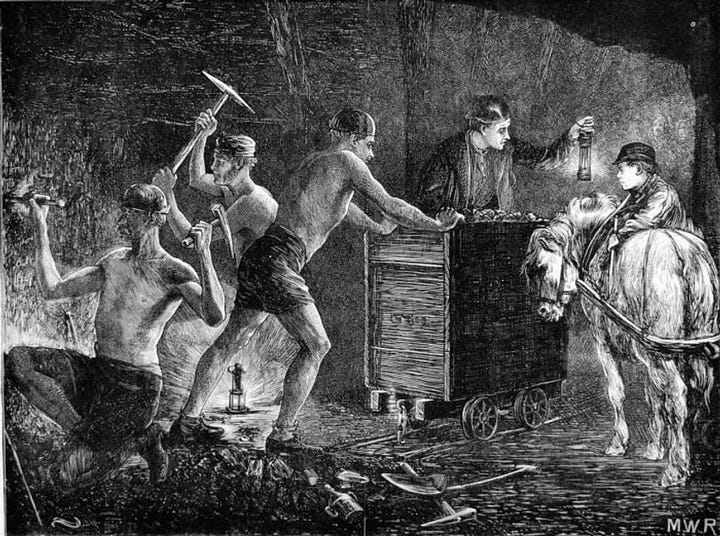

Although in the census of 1841, the second William Makepeace was working as an agricultural labourer, he was 73 years old so I imagine he had been a miner but had been obliged to give up because of his age. In that same census his son Joseph, George Valentine’s grandfather, was a screensman, employed to sort and clean the coal. A picturesque phrase describes the miner as being ‘like a mole groping in the dark, burrowing in darkness’2, and it was somehow fitting to discover that two of Joseph’s brothers were mole catchers. I am somewhat susceptible to claustrophobia and I find it almost impossible to read the descriptions of miners crawling for miles along tunnels just a couple of feet high, to reach the coalface where they knelt or lay for hours hewing the coal, pausing only for a swig of cold tea and a mouthful of bread and dripping, stripped to their underwear and streaming with sweat because of the heat, urinating and defecating where they lay, surrounded by rats and other vermin. These two images are at least a hundred years apart but even with mechanisation not much had changed in the working environment.

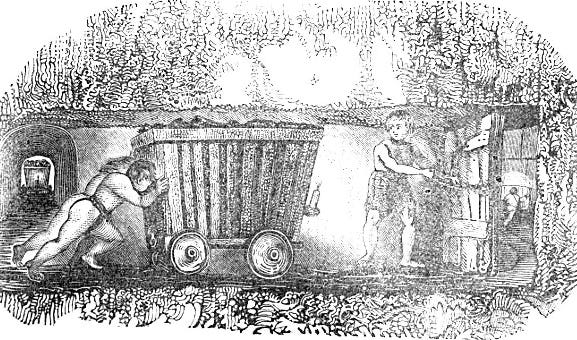

But on the whole pay was good compared with other manual labour and despite (or perhaps because of ) the danger, pitmen saw themselves as a cut above the rest of the working class. Joseph’s son, William Makepeace number three, was George Valentine’s father. Following him through the ten yearly censuses, I learn that he was a coal miner in 1861 but by 1871 he had become a coal weighman. This meant that he was responsible for checking that the amount each man had extracted was correctly weighed at the surface so that he could be paid appropriately. This was a post for which you were chosen by your fellow miners so he must have earned the trust of the men around him. George had six older brothers, five of whom went down the mine, probably by the time they were ten years old. The days of five year old children sitting for long hours alone in the dark, opening and closing the wooden doors to control the flow of air, had ended thanks to the Mines Act of 1842, which prohibited the employment underground of children under the age of ten (raised to twelve in 1860). In 1861, fourteen year old William and twelve year old Ralph were both listed in the census as pony drivers. This was often the first job a boy was given, managing the horses that pulled the tubs of coal from the coal face. There were up to 200,000 of these animals stabled underground and rarely hauled out, with great difficulty, for a brief holiday in the fields. It was said that the ponies were better cared for than the boys, but there were no proper regulations against abuse till the 1870s.

The 1842 Act also banned women and girls from the mines, although they could work at surface jobs such as sorting the coal, and George’s sister Elizabeth found work as a servant. Of the brothers, Joseph, William, and Thomas continued working as miners and so did Ralph, who emigrated to Illinois. There were few alternatives to following your father down the pit, but it was not impossible to find other work. John became an insurance agent and Robert left the pit to work in a shop, ending up as a successful building contractor. The army, then as now, offered adventurous lads a way to leave home and George’s younger brother Wilson joined the Grenadier Guards. Family legend has it that he was one of Queen Victoria’s bodyguard.

Mines were often small, local, and not long lived, so miners were nomadic, moving around to follow the work and the associated peril. Accidents killed 85,000 British miners in the years 1853-1953. It is likely that the Makepeace family had left Trimdon by the time of the famous disaster, one of the hundreds that occurred with terrifying frequency. In the case of Trimdon Grange, a mine employing 700 workers, it was an explosion, thought to be caused by firedamp (an inflammable gas, mostly methane) being ignited by shot firing, that killed 74 men and boys, the youngest just twelve years old, on 16th February 1882.

I know that by 1887 the Makepeaces had moved north to Marsden, a village on a clifftop below South Shields that owed its existence to the Whitburn colliery, which opened in 1874. 700 people lived in 135 isolated and windswept houses, two up two down or smaller, spread along nine streets. Perhaps understandably many miners preferred to live in South Shields and travel to work on the Marsden Rattler. This was the nickname for the train that ran on the Marsden railway, built by the colliery to carry coal and limestone from the nearby quarries that it also owned. The miners travelled in three shabby, second-hand carriages that had been stripped back to provide nothing but basic wooden seating and bumped and rattled along in a most uncomfortable way. There is more information and images on the Disused Stations website.

Other mining families moved into the misleadingly named Marsden Cottage. This was not a cottage at all, but a large country house that had been acquired by the Harton Coal Company and converted to provide accommodation for 67 men, women and children.3 William and Martha Makepeace were living at Marsden Cottage with their youngest son, James. The next youngest, Wilson, was back home, either on leave from the army or having left permanently, when the two brothers went for a night out in South Shields. They caught the Marsden Rattler to come home at about 2am on 1st October and jumped off as it passed Marsden Cottage, as appeared to be common practice amongst the men who used the train (the official halt for the residents of the Cottage didn’t open till a few years a later). Tragically, Wilson stumbled (had he perhaps been drinking?), fell under one of the carriages and was crushed by its wheels. The Shields Gazette reported that:

He was conveyed to the Ingham Infirmary, where he died shortly after six o’clock. The body was afterwards conveyed by four men to deceased’s home, Marsden Cottages. His mother, an old woman 62 years of age, on learning of her son’s death, fell down and instantly expired.

Wilson and his mother Martha were buried together in the graveyard of St Peter’s Church, Harton, in what must have been a devastating blow for the family. Mining was a dangerous occupation, but this must have seemed like a senseless accident. And more was to follow. Although William remarried a local widow in 1889, the following month he lost another son. According to the report in the Shields Gazette, On 27th November 1889, James, an assistant weighman, was pushing a truck off the weighing machine when a heavy waggon full of coal rolled into him and crushed his thigh. This could only have happened if someone had let the brake off. There was one witness, a young boy who worked as a letter carrier at the colliery, and he testified that he saw a man get down from the train and release the brake. The only possible culprit was the guard, a man called John Millett. He failed to own up and was censured by the coroner, who told him that although he had no intention of causing the accident, it would have been ‘more manly’ to have confessed the truth.

The coroner had more harsh words to say. James had his leg amputated the following day but it was too late to save him. Three doctors had advised amputation but his friends (a word used at this date to refer to family) had refused to allow it. The coroner said, in an interesting commentary on how doctors were viewed at the time:

He wished to bring these facts out, as it was essential that friends should know – however desirous they might be to preserve a limb, and whatever might be the matter of sentiment against an operation being performed – that the doctors were the best judges of what was necessary to be done. It was a great mistake to suppose that members of the medical profession could have delight in cutting and hacking injured people. That was not the fact, although there was a common idea to the contrary, and it was very desirable that the idea should be dissipated.

James was remembered as ‘well known in connection with temperance concerts and entertainments for charitable objects in South Shields. Did he perhaps give up alcohol after Wilson’s death, or is that taking speculation too far? His funeral procession was enormous and included members of the Baring Street Primitive Methodist Choir, of which he was a member.4 The following July a Grand Concert was given in the Gospel Temperance Hall in aid of a fund for a memorial to his memory, but I’m not aware of any memorial other than his headstone in the churchyard. Headstones were (and are) expensive and the fund may have paid for this one. There is certainly no trace of a stone for his mother or brother. The village of Marsden itself was demolished in the 1960s after coastal erosion meant it was in danger of slipping into the sea and the Marsden Rattler survives only as the name of a pub.

George Valentine had married the month before James died and in 1891 he was living in South Shields, listing his employment as ‘colliery banksman’, the man in charge of signals and cage loading at the top of the shaft, a job that he held until his retirement. Again, I don’t know if he chose to work above ground or if his heath failed, but it seems that in general, surface workers were of lower status than the hefty hewers who toiled at the coalface. George and his wife Mary Jane went on to have seven children, two girls and five boys. The oldest of their daughters was my grandmother Ethel.

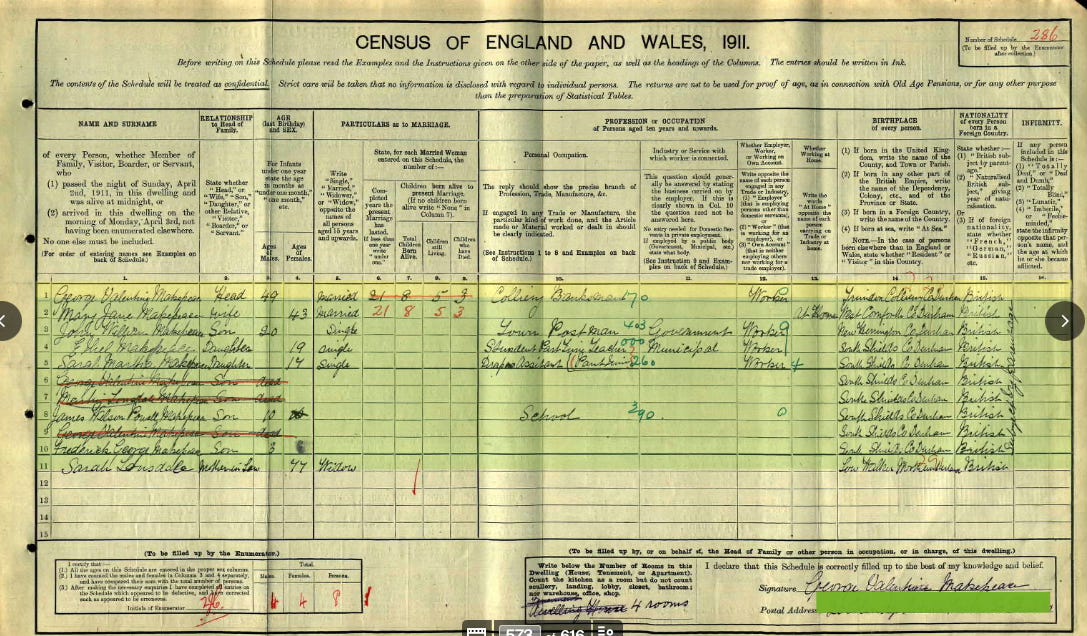

Life was precarious for children at that date and in those communities and three of their sons died in infancy: Martin aged seven, and two babies both poignantly named George Valentine, born in 1896 and 1903 and dead within a year. I only discovered their existence when I examined the 1911 census and saw their names crossed out and the word ‘dead’ written in. But the children that survived did well for themselves. Ethel was employed as a student teacher in 1911 and her sister Sarah was a draper’s assistant. They were both to marry well. The oldest son John became a postman. He survived the carnage of World War I and lived to be 67. The next boy, James Wilson Makepeace, named for his two dead uncles, became a motor man at the St Hilda colliery, also in South Shields. I think this may be the same as a winding engine man, a skilled job in charge of the winding engine that hauled the coal and men up to the surface. And the youngest boy, Frederick, did the best of them all. He trained as an engineer and travelled the world;. I’ve found records for him on ships sailing to Yokohama and Port Said.

But the economic slump that followed World War I meant a steep drop in the demand for coal and the British government returned the mines, which it had effectively nationalised during the war, to their previous owners, who decided they had to cut miners’ pay. The miners’ response was to call a strike, which led to them being locked out: either they had to accept lower wages or be sacked. The crisis known as Black Friday resulted in the 1921 census being postponed, and when it was finally taken in June instead of April, page after page of miners, including George Valentine Makepeace and his son James, recorded themselves as being out of work. The General Strike that followed in 1926 was again triggered by a dispute over miners’ pay, and by 1934 a quarter of a million miners had lost their jobs. The industry was in crisis and in !938 the Coal Act was passed, effectively nationalising the mines and paying compensation to the landowners. By that time George Valentine Makepeace had retired and was living in Newcastle with Frederick, who was working as an inspector of armaments ordnance fitter and, I would guess, employed by the giant firm of Vickers Armstrong. The act was due to come into effect in July 1942. Six months later George was dead. After livingthrough the heyday of the coal industry, he had witnessed the beginning of its terminal decline.

There is a wealth of resources available for anyone wanting to research the coal miners of the north east. Online I consulted the Durham Mining Museum, the Northern Mine Research Society, and the Coalmining History Research Centre. I don’t know where we’d be without the enthusiastic volunteers who collect and maintain these databases. A useful book to start with is Tracing your coalmining ancestors by Brian Elliott and Jeremy Paxman has written an informative and robustly readable account called Black Gold. As more general background I enjoyed reading The Northumbrians by Dan Jackson.

This post is public so please feel free to share it. I’m off to Northumberland next week and hope to visit Cragside, so look out for a post about Sir William Armstrong, the founder of Vickers Armstrong, and the Elswick works, where my grandfather Wilfred, Ethel’s husband, was employed.

After the tin mines closed.

Doc Davies quoted by Jeremy Paxman in Black Gold.

1911 census

Most miners adhered to Nonconformist religions, especially Primitive Methodism.

Fabulous work! The research, the context, the storytelling - all of it! Thanks so much for sharing this piece and putting it out there as yet another way to tell family history.

Wow this is my favorite kind of family history, and the kind I aspire to write. I was very moved by their lives and immersed in their world, and learned so much about miners and mining!