Happy new year and welcome to my first post of 2025. My Christmas tree is now outside, waiting for the next recycling collection, and I’ve run out of mince pies, so it’s time to get back to the business of story telling. I haven’t been entirely idle over the past couple of weeks, however. I’ve imported more posts into the Place writing section, which you might like to dip into. Stitches in time, for example, is all about the textiles of Uzbekistan while On the trail of William Morris is set closer to home, and is about the neighbourhood where I live.

In this post I return to the family featured in A Cornish Cargo. After the book was published, I found it hard to say goodbye to my characters. I knew that if I followed them through to the next generation, there were plenty more stories to be told, but my original intention was to write a Victorian book and after all, I had to stop somewhere. Rather than embark a sequel, which could end up as an increasingly bitty set of anecdotes, I thought I would use Substack to share some of my research into the next generation of Dupens.

I’ve written at length in my book about John Wesley Dupen, the third son of Johanna and Sharrock, who was named for the great Methodist preacher. I imagined him as a studious and dutiful boy, and I knew that he began the family's engineering tradition when he became an apprentice in Harvey's foundry. After completing his apprenticeship, John left Hayle to join the navy, where he rose to the rank of Chief Engineer, dying in 1888 when he was only 44. His wife, Julia Spray, was the daughter of Phillips Biggleston Spray, a master mariner who became the Hayle harbour master and later a shipping agent. They had six children, the births widely spaced because of John’s long absences at sea, and lost their oldest daughter Mary to croup (probably diphtheria) at the age of four. Mary was remembered in the family as a ‘very remarkable’ child, which I think may be another way of saying precocious. My great-aunt Lulu remembered Mary’s verdict on her mother Julia, that ‘she could hardly love her mother, she was so foolish.’ A view enthusiastically endorsed by Lulu, who added that she ‘couldn’t agree more!!!’. It is an unfortunate feature of family history, that sometimes only random and unflattering memories survive.

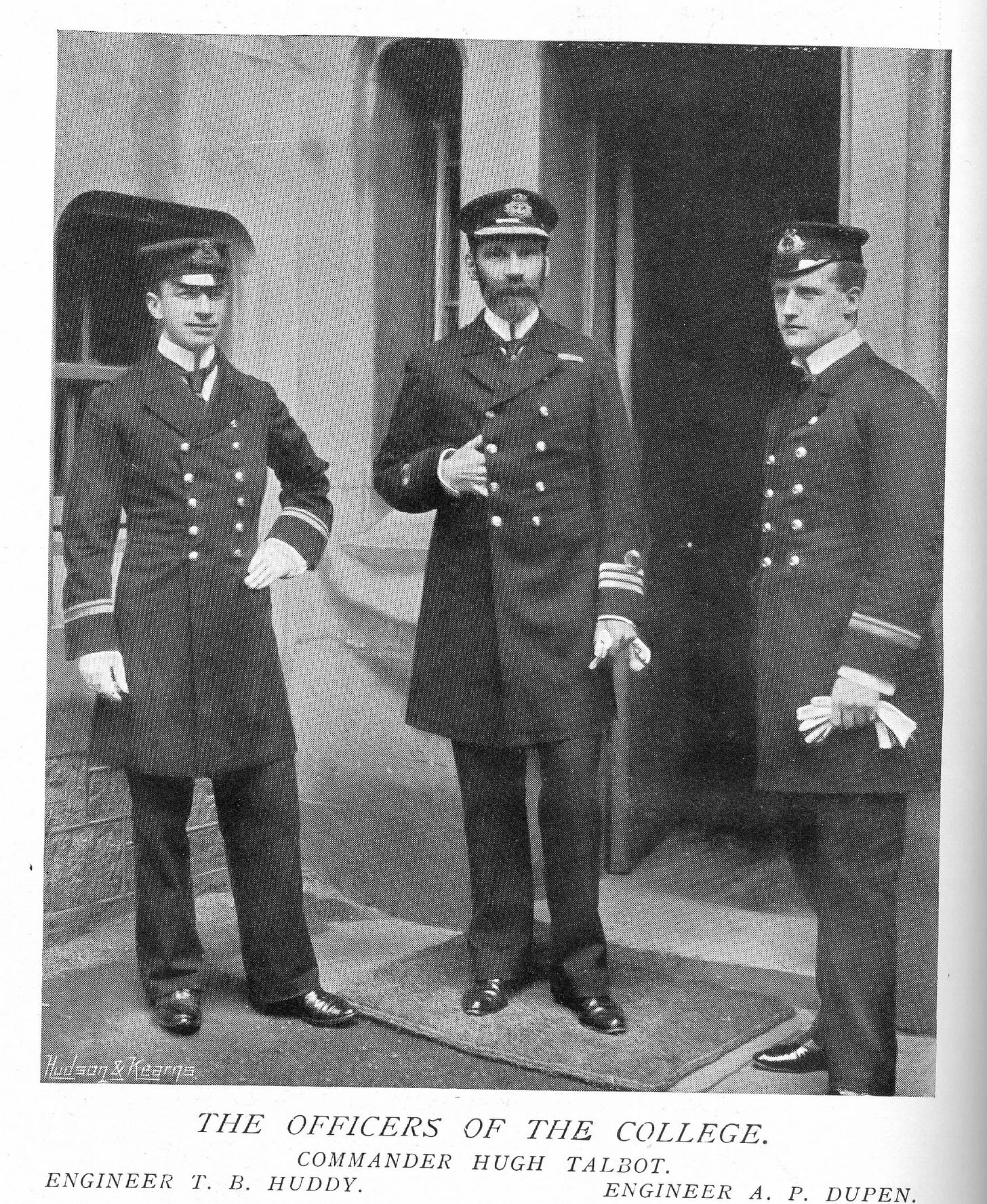

When John Dupen died, his oldest son Arthur Phillips Leslie Dupen, was a naval engineering student. At the bottom of John's naval record is a note to say that the navy turned down a request from John’s widow to reduce Arthur’s fees. The money must have been found from somewhere because Arthur went on to become an even more successful naval officer than his father, achieving the rank of Engineer Captain. He served on the China station around the time of the Boxer rebellion and was at one point a fencing instructor at the naval training establishment in Portsmouth, a fact that I discovered thanks to a helpful acquaintance who has written a history of naval swords and swordsmanship. He also supplied me with a photo of Arthur.

Arthur married Florence King, the daughter of a prominent Freemason. According to their oldest son, another Arthur, she was a wealthy woman and ‘an arrant snob’. He excused this by saying that this was not intended to be detrimental to her character but:

She lived in an era when snobbery or social distinctions were not only expected but were necessary. The wife of a high ranking officer in the navy simply had to conform to the customs of the period or he did not get promotion.

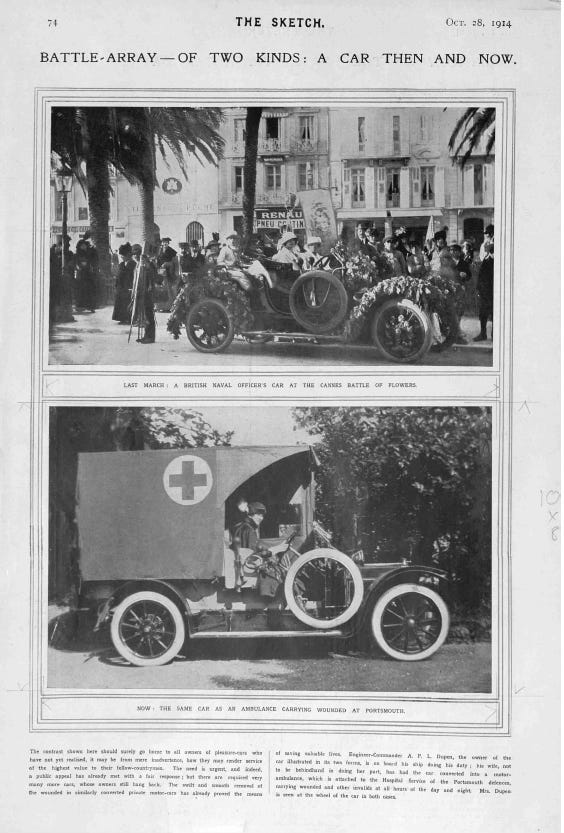

The couple acquired an extremely smart motor car, pictured in an article in The Sketch shortly after the outbreak of war in 1914. In the first picture, Florence is shown at the wheel of the car at the Cannes battle of flowers. In the second image, she is driving the same car, but this time it is being used as an ambulance to transport the wounded in Portsmouth. The accompanying text urges all owners of private ‘pleasure-cars’ to offer their vehicles to be used in the same way and thus save lives.

Fencing and motoring were not the only gentlemanly pursuits that Arthur Dupen enjoyed. He survived World War I, only to fall from his horse while playing polo and fracture his skull on Christmas Day 1918. A tragic and unnecessary death.

Captain Arthur Dupen was buried in Malta, where he was stationed at the time of his death, but he is also commemorated in the graveyard in Hayle together with his younger brother Cuthbert, or Bertie. Bertie’s life could hardly have been more different from that of his older brother. He left Hayle at the age of eighteen, having apparently given up an engineering apprenticeship after less than two years. His destination was Cape Town, but five years later, in 1906, the records show that he sailed from Liverpool to Nigeria. He can’t have stayed there long because according to his nephew, he was employed by the Eastern Extension Cable Company on the Cocos islands, a remote archipelago 2,000 miles west of Darwin and a critical link in the growing telegraph network that connected Australia to the rest of the world. Subsequently he ‘took up a block’ in the wheat belt of Korrelocking west of Perth, but the 1913 census shows him working as a farm labourer in Dampier, in the remote north of Western Australia. A year later, at the age of 32, he joined the army.

The Australian Imperial Force was established in August 1914 soon after Britain declared war on Germany, recruiting volunteers to fight on behalf of the British Empire. Cuthbert would have been one of the 32,000 enthusiastic volunteers who passed through the Blackboy camp east of Perth. But instead of being deployed to the Western Front, a combined corps of some 60,000 Australians and New Zealanders (Anzacs) were sent as part of the Mediterranean expeditionary force to try and take control of the Dardanelles, the strait that links the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

They landed at Gallipoli in April 1915 in appalling conditions, fighting their way up steep cliffs against a much stronger Turkish defence than expected and ended up dug into trenches where they were plagued by heat, poor sanitation, and flies that feasted on unburied corpses and spread disease. Dysentery was rife.1 Over the next eight months, the Anzacs advanced little further than the positions they had taken on that first day of the landings. More than 8,000 Australians died, including Private Cuthbert Dupen of the 11th Battalion, who was killed in action on 28th June 1915.

Captain Arthur Dupen’s widow, who strikes me as being rather dashing, went on to marry a man who had served as a lieutenant in the 7th Hussars, and trained as one of the early military aviators. Her twin daughters were debutantes whose engagements and weddings featured in society magazines The Tatler and The Bystander. Her son Arthur Vivian Dupen, who was only thirteen when his father died, was sent to Rugby, the famous public school, and claimed to have been largely brought up by his aunt Elsie because his mother was busy with her social engagements. It is perhaps unsurprising that he rebelled against his upbringing, emigrating to Australia like his uncle Bertie at the age of 17. He started out as a cattle station hand but by the 1930s had become a minor celebrity. It was perhaps his upper class British accent that had got him the job of chief radio announcer for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

In 1966, by that time in his sixties, Arthur Vivian Dupen was writing from Queensland to a distant cousin in Sydney, yet another Arthur, to exchange information (much of it erroneous) about their family history. His letters have survived and tell a rather sad tale of failing in the real estate business, being too old to get another job, and being deeply dissatisfied with his daughter’s boyfriend, who is only an Able Seaman, because ‘we have always been an officer family’. I already knew that he lost his only son (yet another Arthur) to a tragic accident when he was only twelve, and I felt sorry for him in an abstract sort of a way, but it was reading his own words that brought him to life as a real human being worthy of compassion, not just a series of genealogical facts. Like his uncle Bertie and so many other young men of that time, he was a restless soul, telling his cousin that he had lived in every part of Australia apart from Tasmania.

Arthur Vivian was too young to have served in World War I, although he was an officer in the Royal Australian Airforce in World War II, but it turns out that Bertie Dupen was not the only Dupen at Gallipoli. Arthur Henry Dupen, the cousin in Sydney, was old enough to enlist in 1914. He was working as a nurseryman in New Zealand and joined the 3rd Auckland Infantry Battalion. He was part of the Anzac force sent to Gallipoli and was wounded on 12th June 1915. He was wounded again in 1916 and must have returned to Australia in 1917 because in July 1918 his record shows that he re-enlisted, this time in the Australian Imperial Force, having served for three years with the New Zealand forces. Unfortunately his side of the correspondence has not survived but he seems to have mentioned to his cousin that yet another Dupen, Tom (who I haven’t as yet been able to trace), was also at Gallipoli, eliciting the comment from Arthur Vivian, ‘Not a bad record for such an uncommon name’. It is indeed an unusual name and it is perhaps fitting that it now survives only in Australia.

If you want to read more about the Victorian Dupens, to mark the start of a new year I’m running a price promotion on the kindle edition of A Cornish Cargo. For one week only, from 9th January, it’s available at the bargain price of 99p.

On the Scottish side of the family, my cousin Steve Smythe has written on his website Barrowsgate about his grandfather Jim’s experience of Gallipoli. Jim was about the same age as Bertie Dupen and had an equally adventurous life, travelling all over North America and Australia. He joined the 10th Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force so the two men would not have met, but they had a lot in common.