Uzbek style is all about the bling. Whether they are wearing a full-length gown and headscarf or jeans and a t-shirt, the women of Uzbekistan dearly love a bit of glitter. A scattering of sequins or a few diamanté buttons provide the finishing touch to an outfit that is already bright with colour and pattern. In the Fergana valley, we visited a factory where they weave the traditional ikat fabric still worn by women of all ages. The feet of the most experienced workers pedal away at their eight treadles faster than the younger ones manage with just two. The warp threads are dyed before they are set on the loom, producing a softly blurred edge to the design that is instantly recognisable. In Margilon they pride themselves on their use of natural dyes extracted from fruits, nuts and insects rather than harsh modern chemicals. Their palette is made up of fresh greens and yellows and autumnal browns and oranges, mingled with dull reds, soft pinks, and vivid indigo blue.

In a back street in Khiva I went looking for the silk carpet workshop set up in 2001 by Christopher Alexander with support from UNESCO to provide work for local women. His book A Carpet Ride to Khiva tells the story. Here too they use natural dyes and traditional patterns to create tufted images that bring to mind the tiles and carvings of the city’s mosques and madrassas.

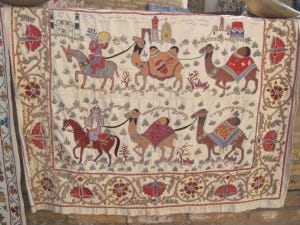

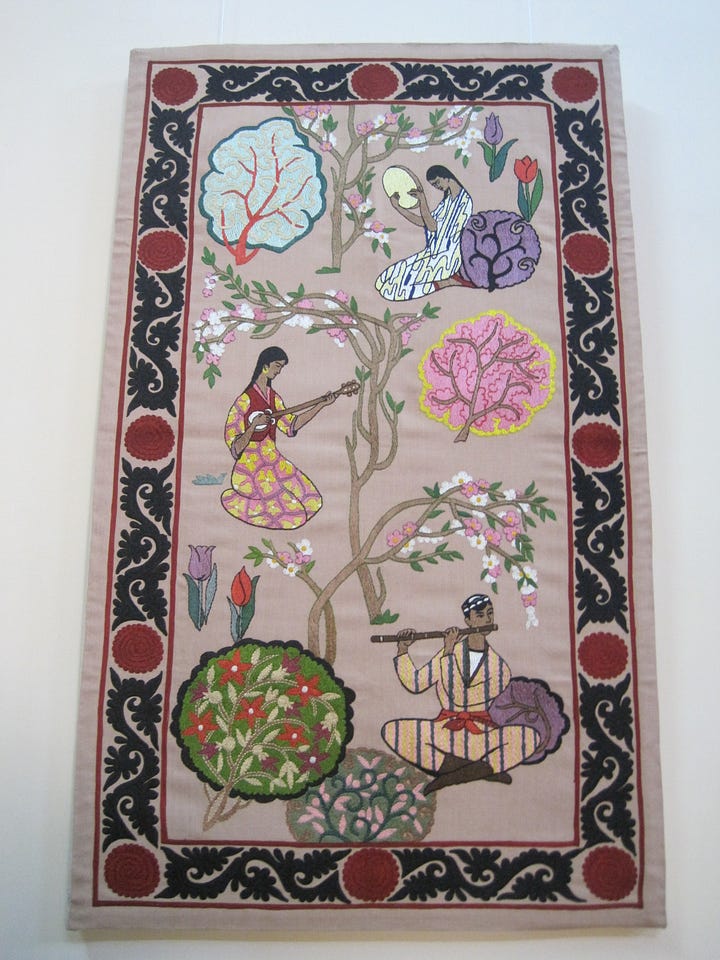

Along the alleyway I stopped to speak to a dark-haired young woman who sat on a stool in the doorway of a shop, her embroidery stretched on a frame in front of her. The suzani takes its name from the Persian word for needle and includes appliqué as well as forms of stitching familiar to generations of women the world over. Chain stitch, stem stitch, couching and cross stitch are used to create a garden of pomegranates, peppers, and the cotton flowers so essential to the Uzbek economy.

Later, amidst the carved wooden pillars of the Juma mosque, we saw women knitting cheerful socks from modern acrylic yarn. Materials may change but techniques don’t.

From his room in the Tilla Kari Madrassa at the heart of the great Registan square in Samarkand Dilshot Adulhaev sells embroideries old and new. With its bookshelves built into the walls and small fireplace in the corner, the room must have been a cosy home for the teacher who lodged there in the days when young men came to the madrassa to pursue their religious studies.

Dilshot spreads out his collection of bedspreads and hangings, including an unusual village suzani with a parade of insects, birds and snakes around its border, and a riot of red and blue flowers on the black background typical of Samarkand. He explains how designs have evolved over time, so that the soporific seedhead of the poppy has morphed into the fertile pomegranate and a magical oil lamp has turned into a mundane teapot.

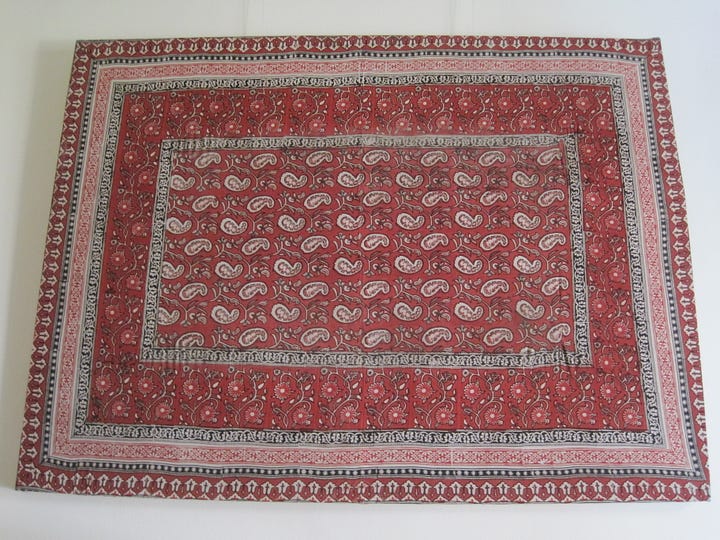

Our final destination was Tashkent, where the Museum of Applied Arts displays wood blocks darkened with age that were used to print on cotton, and above the glass case examples of the patterned cloth.

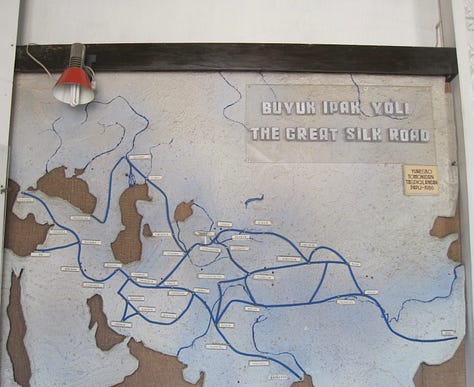

But you don’t need to go to a museum to find the fabric of history. The Silk Road still spins a strong thread across the deserts of Central Asia, kept alive by the busy fingers of the women who stitch together the present with the past.