This post would have been with you much earlier if it wasn’t for the glorious sunshine that we’ve been having in Oxford. The outdoor pool has opened and I’ve been for my first swim of the season, the fritillary meadow is in flower in Magdalen College, and I’ve been tidying up my garden.

I’ve also been packing up a parcel of documents to send to the International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) in Lincoln, where they will be scanned and added to the digital archive. They comprise the logbook, letters, and other papers belonging to, or about, the uncle that I never knew. My father’s younger brother Malcolm was killed in June 1943 at the age of just twenty-one, piloting a Halifax bomber that was shot down over the North Sea, off the Dutch island of Texel. I was born seven years later, and growing up, I knew that Malcolm was a hero who died defending his country against the Nazis. He was one of more than 55,000 men from Bomber Command who were killed (nearly half the total number who served). Many more were taken prisoners of war. They were all volunteers and their average age when they died was twenty-three. As a historian, I welcomed the opportunity to preserve this material in another format. After all, family papers stored in dusty attics fade and decay, and future generations, who don’t have the same personal connection to their content, may not value them as I do. It also felt important to make Malcolm’s story more widely available alongside those of others, to bring the terrible statistics to life. But I suppose it could be viewed as an invasion of privacy; after all, he wasn’t writing for publication. I’d be interested to hear if other people face similar dilemmas about their family papers.

In researching this essay I had to confront another issue. Family history, like any other sort of history, is subject to revision and over time, the simple message of my childhood has become more nuanced, although I still think that Malcolm was incredibly brave. Bomber Command is not as problematic as the colonial history I wrote about in A passage to (and from) India and the pendulum of public opinion has now swung away from what was for a while fierce condemnation, but controversy surrounds the Allied bombing campaign against Germany, and particularly the man who became known as ‘Bomber’ Harris. The introduction to an article published in 2011 summarises it like this:

No aspect of World War II has been more hotly debated, or so misunderstood, as RAF Bomber Command’s offensive against the Third Reich. Until the 1990s, the nearly universal view was that the campaign had been a costly failure, consuming resources that would have been better used elsewhere. This still-prevalent view maintains that Bomber Command’s raids had no significant impact on Germany’s war effort. Critics condemn Bomber Command and its commander, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, for unleashing a brutal and immoral campaign designed to kill civilians, undermine morale, and force the Nazi regime to sue for peace. In this dominant narrative, brave airmen were sent to do a job that was operationally ineffective and morally reprehensible.1

I’m not a military historian but as I understand it, at the beginning of the war, bombing raids aimed at destroying strategic targets such as factories, railways, and fuel depots, took place in daytime and led to heavy losses, but night raids often proved to be inaccurate. Air Chief Marshal Arthur Harris took over in 1942 and instituted new tactics that sent huge numbers of planes to ‘area bomb’ not simply industrial sites but whole towns and cities. They carried not only high explosive bombs but also incendiaries, since fire was the best way to destroy buildings and infrastructure. This culminated in the most controversial raid of the war, in February 1945, when the German city of Dresden was obliterated, killing 25,000 people and fuelling debate about the morality and effectiveness of the bombing. It’s become commonplace to point out that we can’t judge the actions of the past by the standards of today, but in this context it’s worth remembering that people were fighting for survival and wanted the war to end as quickly as possible. The Battle of the Ruhr, where my uncle died, had a real impact on weapons production. The ethos of the IBCC is to promote recognition, remembrance, and reconciliation. A summary on their website states that the men of Bomber Command were fighting for freedom, they significantly changed the outcome of WWII, they did great damage to the industrial capacity of the enemy, and proved vital to the boosting of the morale of the Allies. A final sentence adds that ‘Recognition must also be given to the civilians who suffered as a result of the Command’s campaigns.’ I can only tell Malcolm’s story and I wrote a short version of it in my book, Another Song at Sunset. Others are better placed to relate the lives of the innumerable civilian casualties. But each one was a life that ended too soon.

When I was a child nobody ever talked to me about Malcolm as a person. It was still too painful. What I know of his personality I’ve gleaned from his letters and other documents. Malcolm was born on 11th December 1921. As was the expectation in an English middle class family of the time, he was sent to boarding school when he was only seven. His parents preserved his letters home with their round childish handwriting, misspellings, and occasional illustrations. I’ve chosen to include this one because of the poignant drawing of a plane with an anti-aircraft gun.

Malcolm was musical, artistic, and a keen scout, but not much of a scholar. His school reports tended towards the ‘could do better if he tried’ variety. He passed his School Certificate with a very average C (and a fail in history) so was not thought to be university material. His future was a source of some concern to his parents and they commissioned a vocational report from the Friends Appointment Board (his school, Leighton Park, was a Quaker one). The report describes him as a good conversationalist with a sociable manner, but not ‘a person who shows marked enthusiasm or enterprise in his activities’. A recommendation that he try business work is tempered with the advice that he lacks the necessary ‘pushfulness’ and insensitive nature. Malcolm was eighteen when he started an office job in London with the Anglo-Saxon Oil Company, which ran transport and storage for the Shell group, and moved to live at Shell’s Lensbury Club in Teddington. If he did well, he had hopes of being sent somewhere more exciting, like South America. But it was 1939 and whatever life plans he had were overturned by the outbreak of war. His call up papers arrived in 1940, just before his nineteenth birthday.

The RAF sent him to Blackpool to learn to be a wireless operator but for possibly the first time in his life he found an enthusiasm. He wrote home to say:

I rather want to fly now. Do I have your leave to go through the flying course after my course here? I want to get in as w/op and fly, then if I really like it, re-muster to become a pilot.

He achieved his transfer to flying school the following year and enjoyed the long months of training, as his letters home made clear. He progressed from small training planes like the Miles Magister and the Oxford to bombers. Night flying was jolly good fun and throwing a two-engined Wellington bomber around the sky was excellent fun. Getting lost was a game – you just landed in a field near a fine looking house to be in with a chance of a good meal. When he wrote about ‘climbing up to the cool heights and peacefully gliding down’ it was almost poetic. On the other hand he struggled with the maths he needed to pass in navigation and sent an urgent plea for assistance to his big brother. I have the letter my father wrote back, full of helpful explanations and diagrams, and wonder if he ever regretted his part in helping Malcolm qualify.

Malcolm was eventually posted to 142 squadron based in Grimsby. His life was transformed into that strange mixture of danger and normality unique to aircrew. At one moment they were on a bombing raid but a few hours later they were safely at home in the pub. Flying was both physically and mentally demanding and required constant concentration. Lack of oxygen at high altitude meant they needed breathing equipment and, despite being bundled up in multiple layers of clothing, there was a real risk of frostbite in the poorly insulated planes. Combat stress from fear and fatigue was another danger and at its worst could lead to being labelled LMF ('Lack of Moral Fibre') and removed from the station so as not to affect others. Malcolm rarely mentioned the risks. When he first went on ops, he told his parents how strange it was to shake hands with a bloke and then hear he was gone a few hours later. He got used to it though. The happy go lucky boy who was still young enough to describe his bombing technique as ‘wizard’ was becoming hardened by his experiences.

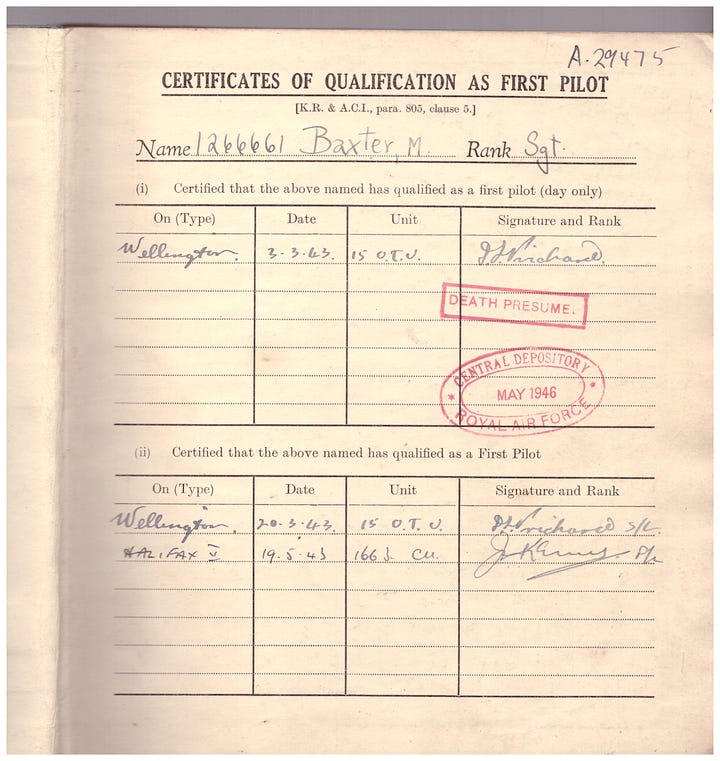

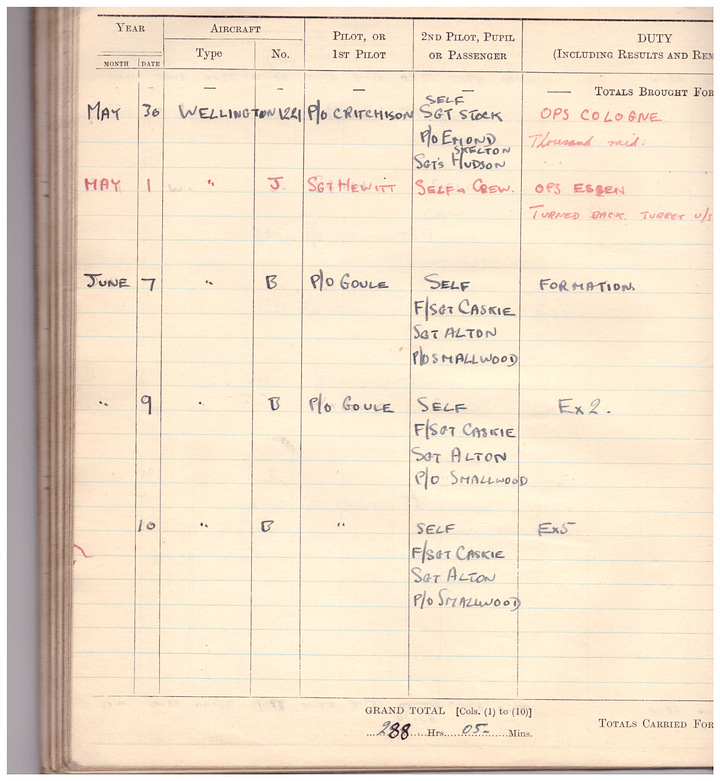

On 8th May 1942 Malcolm made his first operational flight as second pilot, recorded in red ink in his logbook. His entries for that month record operations over the port city of Warnemunde, where they were ‘holed’ by a Junkers 88, and Cologne, with the cryptic annotation ‘thousand raid’. This turned out to be a reference to the historic night raid of 30th May. To reach the psychologically significant figure of 1,000, Air Marshal Harris assembled every possible aircraft (reaching a total of 1,047, of which only 678 were from the main bomber squadrons) and all available aircrew, including instructors and trainees, to fly in a single stream that would overwhelm the German defences and rain bombs, two thirds of them incendiary, on Cologne. The damage caused by the flames was on a scale never before experienced in Germany, destroying not only factories but also schools and hospitals, and damaging some 20,000 homes, leaving 59,000 people homeless. 500 were killed. The following might they did it all over again, this time aiming for Essen, but Malcolm’s plane was forced to turn back because the turret was out of order. At the time, no one was troubled by questions of ethics: the bombing of Coventry in 1940, where a similar number of inhabitants had died and a third of the houses were destroyed, was still fresh in everyone’s mind. Malcolm himself, reacting to a newspaper report about the killing of civilians, wrote that he thought it was a jolly good show after ‘the Nazi atrocities you read about’.

Aircrew were supposed to undertake thirty operational flights before having a six month break, when they served as instructors, but for some reason in June 1942, Malcolm was transferred to training duties. This was dangerous in its own way, as it involved flying with inexperienced trainees in old aircraft, and thousands of men died on non-operational flights. But in 1943 Malcolm applied to return to active service because, as he put it, most of his mates had ‘gone for a Burton’ and it was the only right thing to do. The new plane he was given to fly was a Halifax, ‘a jolly good kite’, and much bigger than the old Wimpey.2 They were manufactured by Handley Page in a factory just down the road from where I grew up in the 1960s, in Radlett in Hertfordshire. I hadn’t quite appreciated how big these planes were until I considered the wingspan – 100 feet is about the length of my back garden. Malcolm claimed that he was becoming quite Halifax minded. They had four powerful new American engines and were better insulated than the old Wellingtons, although they needed watching closely ‘because they bite’. Once Malcolm had completed his conversion course he joined 78 Squadron, based at Linton-on-Ouse, just north of York. The Halifax had a crew of seven: pilot, navigator, bomb aimer, wireless operator, flight engineer and two gunners, mid upper and rear. Malcolm’s crew all held the rank of sergeant, as was usual for men who had completed their training satisfactorily. They were a good bunch, he said, though it was an odd way to put people together, letting them all mill around in a room and chum up amongst themselves. ‘Crewing up’, it was called. He was a bit intimidated by the engineer, who was so much older than the others, at least forty – until he found out the man was a motorbike expert and could tune Malcolm’s machine for him. The bomb aimer was a ‘washed out pilot’, the navigator a ‘darkie from the West Indies’, and the mid-upper gunner ‘a low life definitely befitting to the rest of us.’3 On 23rd May Malcolm flew his Halifax to Dortmund in a raid where the biggest steelworks in Germany was put out of action and 595 people killed. It was his first sight of Germany in a year. ‘Happy Valley,’ he wrote, ‘looks somewhat different. The defences are considerably improved.’ On 25th he was part of a raid on Dusseldorf and his last logbook entry is for 31st May.

On 13th June 1943, barely six weeks after Malcolm had started flying his Halifax, a telegram was delivered to his parents. With devastating brevity it read:

Regret to inform that your son, Flight Sergt Baxter, M. reported missing from operations of the night 12/13 June. Letter follows.

The following day the newspapers reported that after thirteen days of inactivity due to sea mist and fog, the greatest aerial storm yet had broken over Germany. According to the Times, on the night of Friday 11th June 200 American heavy bombers attacked harbours and U-boat yards while ‘the greatest force of four-engined bombers ever sent out by the R.A.F. dropped the record weight of considerably over 2,000 tons of bombs on the Ruhr and Rhineland’. The following night, Saturday 12th June, ‘aircraft of Bomber Command in great strength attacked the Central Ruhr with Bochum as the main target’. Bochum was an important transport hub and heavy industry centre and the newspaper gave more statistics for the attack: ‘The bombing of Bochum on Saturday night was so concentrated that 4,000lb bombs were dropped at the rate of five a minute. Aircraft came over the target in such a constant stream that pilots had to be constantly on the lookout to avoid collisions.’

A total of twenty-four bombers were missing after this raid. One of them was Malcolm’s. ‘Failed to return’ was the official term. More than two weeks after the telegram a formal notification arrived on cream paper embossed with the RAF coat of arms at the top:

Your son Flight Sergeant Malcolm Baxter, Royal Air Force, is missing as a result of air operations on 12thJune, 1943, when a Halifax aircraft in which he was flying as captain set out to bomb Bochum and was not heard from again. This does not necessarily mean that he was killed or wounded, and if he is a prisoner of war he should be able to communicate with you in due course

There was a chance he had baled out, though parachutes were not always reliable and escape hatches were small, meaning that there was only a one in four chance of getting out safely, and if the plane was over water there was the added risk of drowning. Enquiries were made through the Red Cross but no further news arrived. It was my father’s sad task to collect Malcolm’s belongings, travelling all the way to Linton, only to find that the squadron had moved and he had to track them down to their new base at RAF Breighton.

Letters from the families of the other crew members started to arrive. The bombardier’s mother was the first to write. She sent sympathy but like all of them, what she really wanted was information. Everyone hoped that there was news they had mysteriously missed. Mr Payne, the wireless operator’s father, sounded a positive note. ‘These are proud lads and we do really proud to be the parents of such,’ he declared, with more feeling than grammar. The parents of the air gunners, Wright and Westall, sent letters too. ‘Our boy was only 19 years old,’ wrote Mrs Westall. My grandmother did her duty as the mother of the pilot and sent hopeful, encouraging replies. A letter arrived from Jail Alley in Nassau, from navigator Wilbur Jordan’s wife, thanking her for her ‘warm and comforting letter’. She said she felt lucky to have her parents alive and near her, and her children, who were just five and three. Her husband told her Malcolm was his friend. They used to listen to his radio together in the evenings. It was typical of Malcolm to have befriended a man who may well have found himself ostracised by others because of his skin colour.

In November the Air Ministry wrote again: ‘In view of the lapse of time, it is felt that there can now be little hope of his being alive.’ But Malcolm’s parents would not give up hope. Christmas came and went with no news, then the new year. It was a long, cold, winter. Confirmation arrived from the Red Cross that the Germans had recovered the bodies of Payne and Wright some weeks after the raid but the site of their graves was unknown. Mr Wright asked Jean and Harold to write to his business address (a grocer’s in Chorley) to spare his wife the distress of any more correspondence. It was now clear that the plane had crashed into the sea off the coast of Holland, west of the island of Texel, on its way back from the raid. My grandparents could no longer hope that their boy was a prisoner and would eventually come home. They simply wanted a body to bury, but even that was denied them. The rest of the crew members were never found. Thanks to the extremely niche research made possible by the internet, and slightly disturbingly, I have been able to discover that the pilot who shot down Halifax JD 145 was a Major Rolf Leuchs, a fighter ace who survived the war with ten ‘victories’ to his credit. I’ve even seen a photograph of him. He was just doing his job.

I’ll end with a quote from the appreciation Malcolm’s form master wrote in the Leightonian, the school magazine of Leighton Park school:

Malcolm was a very companionable boy, light hearted, often gay, often serious but never stupid or dull […]. He had no enemies whatsoever.

Here’s a link to more about Caribbean aircrew https://media.nationalarchives.gov.uk/index.php/untold-story-raf-black-second-world-war-fliers-europe/

and you can see a photo of Wilbur Jordan here https://www.caribbeanaircrew-ww2.com/?p=70

And this is a book about 78 Squadron https://www.woodfieldpublishing.co.uk/contents/en-uk/p86_nobody-unprepared-history-of-78-Squadron-RAF.html

Dr Robert Ehlers, ‘Bombers, ‘Butchers’, and Britain’s Bête Noire: Reappraising RAF Bomber Command’s Role in World War II’ in Air and Space Power Review, vol. 14, issue 2.

The nickname for a Wellington is taken from a character in the Popeye cartoons.

One in four aircrew came from overseas, mostly Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but there were about 450 from the Caribbean, and many more served as ground crew. They deserve much more than a footnote but I’m afraid this post is long enough already.

You absolutely should be proud of Malcolm. It's easy for people watching from the comfort of the twenty-first century to say Harris' strategy was unnecessary, excessive and ineffective, but nobody knew that at the time and I wouldn't blame them even if they did. Nazi Germany had to be defeated. They did what they thought they had to. I'm not that brave.

Such an impressive amount of research and movingly put together. Poor Malcolm. The death toll in the RAF during WW2 is so high that as soon as I saw your post with his photo, I thought, "Can I bear to read this? He very likely didn't make it." My grandma's cousin Jack died on a training mission when he crashed his Spitfire into a hill in low visibility (Grandma never mentioned him - I found out about him when his grandson got in touch after I put a group photo including Jack as a boy on Ancestry). My grandad's cousin Stanley died when his plane exploded on the runway. It was so, so high risk to be aircrew.

The letters Malcolm wrote home and his school report bring him back to life. Hearing his voice and his gung-ho approach is extraordinary and very moving. Thank you so much for writing this. And for sending off his records for preservation. It's so important these voices aren't lost, after those brave young men lost everything.