Machinery of production, machinery of murder

William Armstrong and the Elswick works

This post would have been with you yesterday if I hadn’t decided to (a) go for a swim in the outdoor pool and (b) watch the tennis. Today it’s little cooler and Wimbledon is over for another year, so I’ve finished off my picture research (often the most time-consuming part of the writing process) and this latest instalment is ready to go.

When I was a child, we used to drive north at least once a year to visit my widowed grandmother - the one whose father was a coal miner. She lived in Haltwhistle, a small town in Northumberland, not far from Hadrian’s Wall. I remember standing on top of the Wall, familiar to me from Rosemary Sutcliffe’s Eagle of the Ninth, and imagining what it was like to be a Roman soldier, watching and waiting for the enemy from the north. Later, my grandmother moved to a small flat next to Saltwell Park in Gateshead. Drives across open moorland were replaced by trips to Whitley Bay for bracing walks along the seafront in the freezing wind that blew reliably in – whether we were visiting in March or August – from the North Sea. We never, to the best of my recollection, travelled to the vast beaches north of Newcastle.

This year, at the end of April, I finally managed to visit several places in Northumberland that I’d long wanted to see, including Lindisfarne, the Farne Islands, Cragside, the former home of Sir (later Lord) William Armstrong, and Bamburgh, his final home. Armstrong was, along with George Stephenson and Isambard Kingdom Brunel, one of the great engineers of the Victorian steam age. At its height, his Elswick works stretched for a mile and a half along the river Tyne and employed one in four of the local working population. One of them was my grandfather, Wilfred Curry Wood, which is what sparked my interest in the industrial history of Tyneside.

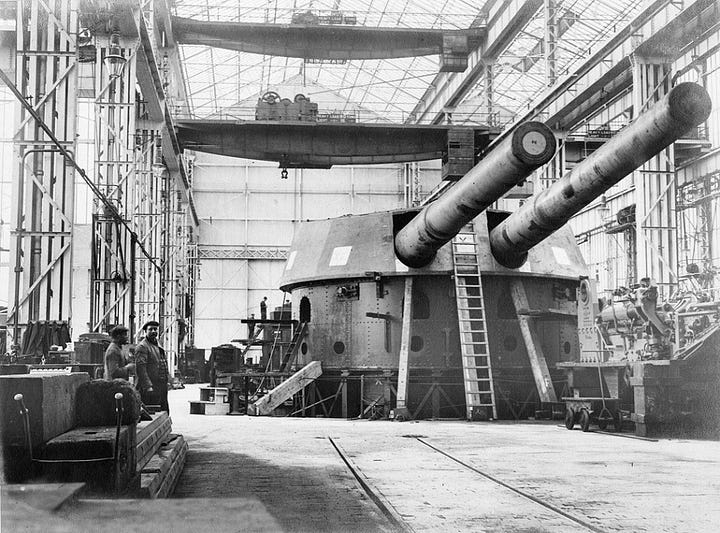

William Armstrong was born in 1810, the son of a corn merchant who was later to become mayor of Newcastle. To please his father, he trained as a lawyer but his real interest was in science and in 1842 he invented a machine called a hydraulic accumulator that could be used to power dockyard cranes, making the loading and unloading of merchant ships much more efficient. Five years later he gave up the law to start a company that manufactured cranes. The Crimean War exposed the difficulties that the British army were experiencing with their heavy field guns and so Armstrong got to work and designed a better one. His company began to manufacture artillery and warships for various countries in Europe and South America. Japan, which was at war with China in the 1890s and Russia in 1904-5, became one of their biggest customers.

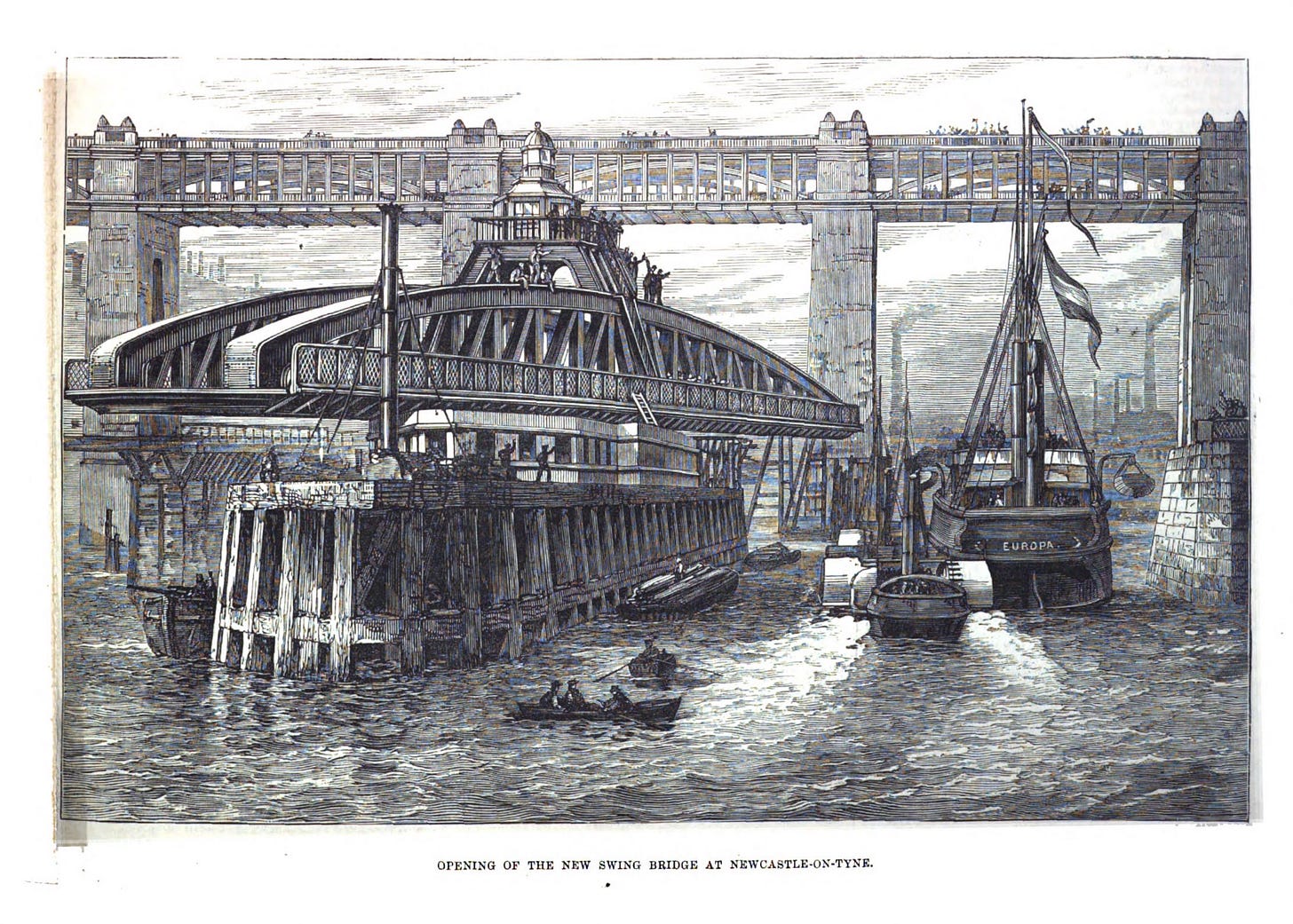

The Elswick works also built steam trains and bridges, including the 1876 swing bridge that connects Newcastle and Gateshead and allowed large ships to pass up the Tyne and reach Armstrong’s factory. In 1887 Armstrong won the contract to construct the seesaw-like mechanism (technical name: bascule) that raises and lowers Tower Bridge in London using steam and hydraulics. In 1882 the company merged with that of shipbuilder Charles Mitchell and opened a yard at Elswick to build warships.

Meanwhile in Manchester, an engineer with a passion for accuracy, called Joseph Whitworth, was introducing a standard size of screw thread and laying the foundations of mass production processes.1 A contradictory character, Whitworth was a pacifist who nevertheless believed in deterrence and had no scruples about manufacturing rifles and cannon. In 1846, Jane Carlyle described him in a letter:

Whitworth, the inventor of the besom-cart and many other wonderful machines, has a face not unlike that of a baboon; speaks the broadest Lancashire; could not invent an epigram to save his life; but has nevertheless 'a talent that might drive a genii to despair' and when one talks to him, one feels to be talking with a real live man. 2

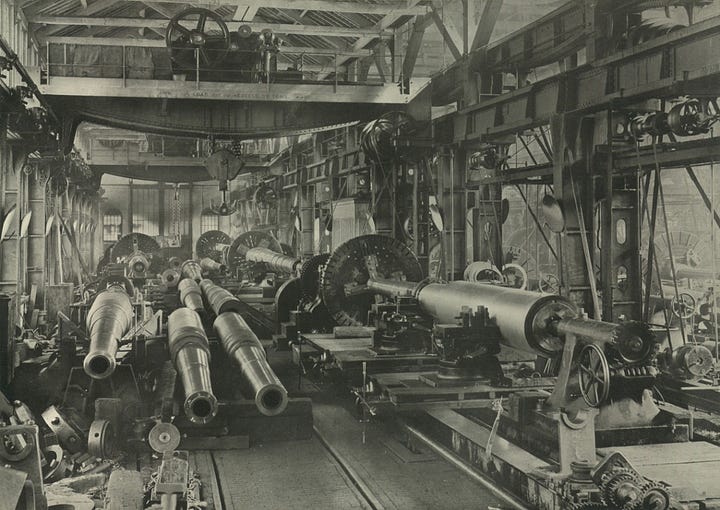

Despite their business rivalry, Armstrong and Whitworth managed to remain on friendly terms and in 1897 the two companies merged to become Sir W. G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co Ltd. The Elswick works went on to manufacture around 6,500 tons of guns, torpedo tubes, artillery and mountings per year and was a major employer of women as well as men. More than 8,000 women worked at Elswick, most of them necessarily young and unmarried.

In the 1850s William Armstrong’s home was in Jesmond Dene in Newcastle, but in 1883 he gave it to the city of Newcastle as a public park and he and his wife Margaret moved out to the village of Rothbury, where he built Cragside, which the National Trust now describes a the first ‘smart home’. It was the first house to use hydroelectricity to power lights, and numerous gadgets including an electric saw, fire alarms, buzzers for servants’ quarters, and dinner gongs.3 Armstrong also planted more than seven million trees and shrubs and created five artificial lakes.

There is much to admire about Armstrong. Although he worked with steam, he saw beyond it to a future powered by water and the sun. He displayed remarkable prescience when in 1863 he predicted that because coal was used ‘wastefully and extravagantly’, Britain would stop mining it within two hundred years. His reputation as a scientist led to his election in 1864 as a Fellow of the Royal Society and in 1887 he was the first engineer to be made a peer. He was also a philanthropist who believed in education for all. and as well as providing schools for his workers’ children, he founded the College of Science, the precursor of Newcastle University. In 1894 he embarked on the restoration of Bamburgh castle, but since he and his wife had no children, after his death in 1900 it passed to his great-nephew and heir, William Watson-Armstrong.

And yet, of course, Armstrong was an armaments manufacturer who washed his hands of any responsibility for the carnage inflicted by his machines, saying:

It is our province as engineers to make the forces of matter obedient to the will of man; those who use the means we supply must be responsible for their legitimate application.

Which is perhaps fair enough, as is the beginning of this second quote, but his final words are indefensible to a modern reader and would quite possibly have been repudiated by at least some of Armstrong’s contemporaries:

We as a nation have few men to spare for war, and we have need of all the aid that science can give us to secure us against aggression - and to hold in subjection the vast and semi-barbarous population which we have to rule in the east.

During the First World War, Armstrong-Whitworth became the largest munitions producer in the world. The company diversified into the manufacture of cars and trucks, and developed the first tank. By the end of the war, it employed 78,000 people. But shipbuilding at Elswick, as in many other northern shipyards, ended in 1920 with the Great Depression. Five years later, a disastrous investment in a Newfoundland power and paper-making facility nearly destroyed the whole business but in 1927 it was saved by a merger with Vickers, a shipbuilding company based at Barrow-in-Furness on the west coast. After Hitler remilitarised the Rhineland in the 1930s, Vickers-Armstrong was immediately ordered to contribute to an urgent re-armament programme, manufacturing weaponry, tanks, ships and planes. The company was praised as a major contributor to the eventual victory of the Allied forces.4

After the war Vickers-Armstrong continued to manufacture aircraft, including the first British V-bomber, ships, including the first British nuclear submarine, steel, and general engineering products. In a complex series of mergers, nationalisation and privatisation, the aircraft division ended up as part of BAE Systems, a major manufacturer of weapons and defence systems, and in 1979 the Elswick works was closed down and demolished.

To return to the family connection, my grandfather Wilfred was the fourth child of Alderman Henry Curry Wood and might have been expected to achieve academic success, like his brother George and sisters Ethel and Henrietta, who all became teachers. But Wilfred followed his father into the Cooperative grocery store, starting as a ledger clerk and rising to the position of manager just before the First World War. He married my grandmother Ethel in 1916 but would have been called up when conscription was introduced for married men in May of that year. He served as a private in the Leicestershire and then London regiments, though without more detailed information I’m not sure exactly where he was sent - it could have been Egypt as well as France. It was in Wilfred’s absence that his father Henry came out of retirement to manage the shop and died on his way to work in 1917.

By the time of the 1921 census, Wilfred was employed at Elswick as an estimating clerk in the marine engines department, calculating quantities and costs. According to the evidence of an old photo album, he must have taken at least one business trip to the east but he never progressed to a management role. Like his father, his great enthusiasm was for cricket and he played for the Vickers-Armstrong team.

I was only four years old when he died and have no clear memories of my grandfather, but in a letter to his parents in 1947, my father wrote a vivid but disrespectful description of his future father-in-law:

Mr W is quite a little chap, bald and with a most intriguing lump the size of a walnut on his crown, just the place where Mabel Lucie Atwell infants grow their single interrogative whisker. He’s alert and humorous but doesn’t say much - not that he had much opportunity while I was there.

Wilfred and Ethel had two daughters and two sons, and my father got the distinct impression that it was the children who had the upper hand in the family home! My mother Doreen, as I’ve explained in a previous post, was an unusual and wrong-willed character. In 1941, as a new graduate in mathematics, she was sent to the radio department of Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) in Farnborough, which is where the engineering heritage of one side of the family meets the other. I’ll write more about the RAE next time.

Whitworth Park, home to the eponymous art gallery, and where I spent a year in the triangular student accommodation we called the ‘Toblerones’, was named after him.

A besom cart was a horse drawn street sweeping machine.

Incandescent bulbs had been invented by Joseph Swan.

For more detailed statistics, I recommend Dan Jackson’s book The Northumbrians, which has a robust couple of pages on Armstrong.

Interesting write up!!

As I was reading, I was wondering whether the Whitworth had any connection with the art gallery- and you answered that in the footnotes. Thank you for a fascinating read.