Today’s post is another one that starts with maritime history and then gets sidetracked. I hope you find these digressions as interesting as I do. As always, please let me know what you think. My writing is free to read but if you enjoy it, do consider buying one of my books, which you can find on my About page here.

I had always believed that my uncle Malcolm, who I wrote about here, was the first pilot in our family. But that was before I found an image of Flight Sub Lieutenant Walter Price. It appears in an album of photographs of holders of Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificate and, surprisingly, it’s dated 1918, when Walter was fifty years old. Malcolm and most of his fellow bomber pilots joined the RAF as boys in their teens and early twenties, but in World War I the enlistment rules must have been very different. I decided I needed to find out more. Years ago I’d dipped into my brother’s Biggles books and had vague memories of dog fights over the trenches, between British Sopwith Camels and German Fokker triplanes, fragile constructions of wood and canvas flown in real life by men like Manfred von Richthofen, the infamous Red Baron. (And if I sound knowledgeable about the planes, that’s also down to my brother, who had a large collection of Airfix models.) But what was the reality behind the stories?

My research took me back to nineteenth century Bristol and another of my grandfather’s many cousins. Walter Samuel Vincent Price, born in 1868, was the second son of Catherine Dupen, known to my grandfather as Aunt Kate.1 She was the only one of the six Dupen sisters not to become a teacher. Instead, she became a draper’s assistant, a job that also required a reasonable level of education in order to measure fabric and ribbons, calculate prices and give the correct change. When she was 26, Kate married a tailor’s son from Bristol called Walter Price. Walter worked as a tallow chandler, making and selling the cheapest kind of candles. Tallow is a foul-smelling animal fat that must have left a lingering stench on his clothes, but after his marriage he opened a grocer’s shop, which I imagine to be a much pleasanter working environment. By marrying Kate, he had acquired a useful wife who could help him with the business, but she would also have been kept busy caring for the eight children (including girl twins) who came along at regular intervals between 1860 and 1877. Fortunately, she had help from her mother and sisters, who took the two oldest girls to be educated at the school they ran at home in Hayle. By 1881, Walter and Kate had taken on the management of the White Lion hotel, a modest establishment in Victoria Street, in the Redcliffe area of Bristol. They sent the twins to their aunts in Hayle. while the two older girls came home and presumably helped in the family business.

Kate’s oldest son was named Sharrock for her father, the ship’s steward who died just a few days before his grandson was born. Young Sharrock didn’t follow in the family tradition but instead, in 1887, he emigrated to Canada, where he worked as an accountant. His younger brother Walter, on the other hand, like his cousin Percy Dupen (who I wrote about here and whose older brother also emigrated to North America), did become a sailor. Sharrock had attended the Queen Elizabeth Hospital school but I don’t know if Walter also benefited from the thorough education provided by this Bluecoat charity school.2 What I do know is that in 1883, at the age of fifteen, he was indentured as an apprentice in the merchant navy in Swansea, just across the water from his home in Bristol.

There were essentially two routes into the Victorian merchant navy at that time: boys from the upper middle class could join one of the two public-school-cum-training-ships Conway and Worcester. Or those from less well-to-do families could enter into a five-year contract as an unpaid apprentice, during which time he would undertake the same duties as an ordinary seaman and learn by observing. There was a general belief that it was best to get boys young, when their limbs were still supple, their reactions fast, and before they had enough sense to be frightened! At the end of his apprenticeship, a young man would sit the examination to become a mate. He had to hope he had learned enough to pass in navigation, since there was no formal tuition in that essential skill, which was carried out using sextant and chronometer to steer by the stars, or in bad weather by dead reckoning, using a calculation of speed and distance.

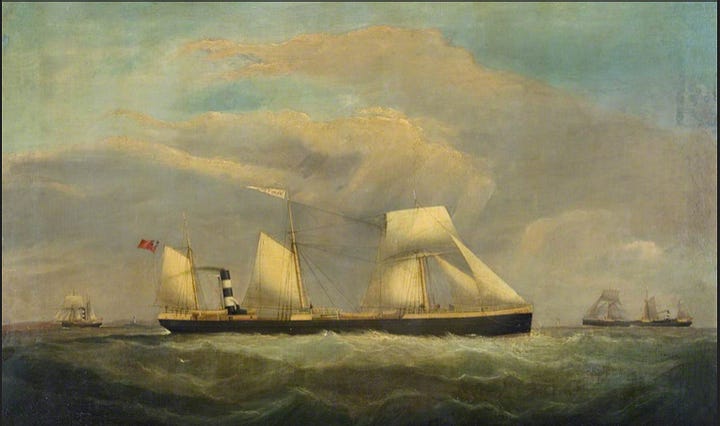

In 1888, two years after his cousin Percy, Walter qualified as second mate of a square rigged vessel. He is described as 5ft 8½ins in height, of fair complexion, with brown hair and grey eyes. He lists his experience as an apprentice on the Campana, a Liverpool-registered barque - an iron-hulled sailing ship with three or four masts, considered to be the workhorse of the British sailing fleet.3 She was one of many such ships that crossed the Atlantic, delivering and collecting general cargo. I found evidence of her calling at Buenos Aires, San Diego, and Iquique, a port on the Chilean coast where guano and saltpetre were the main exports.4 This means that young Walter would have known the often terrifying experience of rounding Cape Horn. This was considered to be dangerous in either direction but much worse travelling west. You could be fighting gale force winds or foundering in an equally risky dead calm; the rigging would be thick with ice and the accommodation flooded. Many ships were lost and Ernest Shackleton described finding a graveyard of wreckage on the island of South Georgia:

Just east of us was a marvellous pile of driftwood, covering half an acre, and piled from 4 to 8 feet high in places. This was a graveyard of ships, woeful flotsam and jetsam, the sport of the sea.5

Three years later, in 1891, Walter qualified as a first mate, with a whole list of different voyages in different types of vessel. For a few weeks he served as second mate on the Jane Bacon, a passenger steamer much like the ones his grandfather and uncle Sharrock had worked on as stewards, which made the round trip between Liverpool and Bristol every Saturday for a fare of 12s 6d (cabin) or 6s (deck). But she was classified as a coastal vessel, and if he was to get a master’s certificate he needed ‘foreign’ experience. He made a six month voyage on the Gloamin, a Cardiff registered barque of a similar size to the Campana. She was possibly employed, as many such sailing ships were, to carry a cargo of Welsh ‘navigation coal’ to the coaling stations set up around the world to provide fuel for Britain’s steamers - supporting the competition, so to speak. Walter’s next ship was a steamer, the Allonby, but after three short voyages he signed on for a year as second mate on board the Newcastle-registered barque Eildenhope. At 1498 tons, she was nearly double the size of his previous sailing ships and was in service on the Australian route. I found a record that showed she made at least one voyage carrying emigrants, but probably also took general cargo.

Walter got his master’s certificate in 1895 and once again the certificate contains details of all his voyages. For a year he served as first mate on the Liverpool-registered barque, River Ganges, which like the Campana collected guano from Iquique, but also made regular voyages to Victoria in British Columbia to collect a cargo of tinned salmon (29,461 cases, but I don’t know how many tins there would have been in a case!) But competition for jobs was fierce and Walter ended up spending a year as second mate on the Sentinel, a barquentine (smaller than a barque, with only the foremasts being square rigged) registered in Yarmouth, on the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia. To my shame, I had no idea what an important port Yarmouth was in the nineteenth century, the second largest port of registry in Canada in terms of tonnage, with a shipbuilding industry dating back to 1764. After a year Walter worked his passage back to England as bosun on the Yarmouth -registered brigantine Aeronaut.

On his return, he sailed as third mate on the steamship Rialto, one of the first steamers built for Messrs Wilson of Hull for their New York trade. The Wilson Line was one of the largest privately-owned steamship lines in the world and carried more cargo to the USA than any other company. Their ships also sailed to Scandinavia and the Baltic States to collect large numbers of emigrants and Jewish refugees from the Tsarist pogroms, brought them to Hull, transported them overland to Liverpool and from there transported them to America. Third mate might sound like a demotion but there was a lot of competition for work with such prestigious companies and you often needed a master’s certificate just to be a mate.

The final ship on Walter’s certificate is the Port Caledonia, a four masted steel barque of 2426 tons registered in Glasgow. He spent almost two years as her first mate, with the only newsworthy event occurring in January 1894, when his ship, along with more than twenty other British ships, was detained in Rio de Janeiro and unable to discharge her cargo as a result of the naval revolt in Brazil (a complicated affair that I’m not even going to attempt to summarise). A firm letter was written by the Clyde shipowners association to Lord Rosebery, the Liberal Prime Minister, urging him to instruct the navy to intervene but I don’t believe they did and presumably the ships were able to get away by the time the revolt was finally suppressed in March. Once Walter had his master’s certificate, of course, there is no further record of his ships but the 1901 census shows that he has taken responsibility for the family after the death of his father in 1889. He is shown as the head of a household made up of his mother and four of his younger siblings, in Chesterfield buildings in Clifton.

There has proved to be an unexpected metallic thread running through my research - or as the Victorian journalist I quoted in my last post called it, ‘an auriferous seam’. Several times when writing about maritime history I’ve found a connection with gold mines. As I wrote in A Cornish Cargo, George Dupen sailed to Melbourne at the height of the Australian gold rush and his ship, the Dover Castle, returned to London with a cargo that included 22,156 ounces of gold. Ernest Dupen wrote about carrying a thousand Chinese labourers to the goldfields of Queensland in 1874 and gave a vivid description of the ‘diggers’ he encountered in Australia. I wrote in my last post about how Percy Dupen spent years captaining ships sailing to the Gold Coast, and now I find that his cousin Walter Price seems to have turned gold miner in South Africa. In 1910 his marriage was announced in the newspapers and he is described as being of Clifton, Bristol, and Bantjes G. M. Florida, Transvaal. I’m guessing that G. M. in the marriage announcement stands for Gold Mine.

In 1884 a Boer called Jan Gerritze Bantjes, son of a famous Voortrekker, was the first of several prospectors to discover gold on land in the Witwatersrand.6 The original mining camp grew into the city of Johannesburg, which by 1895 had a population of 102,000. Mining activity was halted during the Boer war (1899-1902) but resumed with imported Chinese labour, replaced in 1910 by Black workers forced off their lands or migrating from Mozambique and other colonial territories, under conditions that should probably be described as forced labour or bondage. At some point during those years, Walter must have set off to seek his fortune. A passenger list from April 1908 sees him embarking in Southampton for a voyage to Cape Town and describing his occupation as ‘miner’. Skilled jobs in the mines such as blasting and engine driving were reserved for white workers, who were also unionised and much better paid than Black labourers. Between 1903 and 1973, 42,000 men died on the gold mines. Ninety per cent of these were Black African.

Walter and his wife Eleanor had two children, born in 1911 and 1913, and in the summer of 1913 they sailed back to England to stay with his mother in York Crescent Road (now York Gardens) in Clifton, where the children were christened in Kate’s local church. They returned to South Africa about six months later, and in January 1918 Walter is listed as a probationary flying officer in the Royal Naval Air Service, shortly before it merged with the Royal Flying Corps to become the RAF. In March he was promoted to Flight Sub Lieutenant and by November was a full Lieutenant. In 1915, the South African Aviation Corps had been deployed in the campaign against the Germans in what is now Namibia, and over the course of the war, some 2,500 South Africans joined the RFC and the RNAS. Walter’s record shows that he was posted to Roehampton, which was actually a naval balloon training station, a fact I discovered from this fascinating guide to UK airfields. The pilots who manned the balloons were effectively sitting ducks:

Who would want to stand in a tethered balloon a couple of thousand feet or so above a battlefield without any defensive armament at all, directing artillery fire, (a far from easy job), knowing that at any minute you and your balloon might well be attacked by an enemy fighter? In which case you only chance of survival was to leap out and trust a very early and barely proven type of parachute.

Walter served until December 1919, being posted to a number of airfields as far apart as Stromness in Orkney and Boscombe Down in Wiltshire, though I admit to struggling with the handwriting on his record. He was demobbed and returned to Johannesburg, where in 1921 he died of miner’s phthisis, a blanket term for a number of different respiratory diseases but in this case probably silicosis, contracted by inhaling dust from the gold-bearing rock. He was 53 years old.

Samuel would have been for Kate’s brother who died in 1867 and Vincent was a family name on her mother’s side

Bluecoat schools existed all over England and were named for the distinctive uniform of long blue coat worn with yellow stockings.

The best source of information about ships and sailors that I’ve found is the Crew List Project.

Guano is fertiliser made from the excrement of birds, bats and seals. Saltpetre is another name for potassium nitrate, which was used to preserve meat, as fertiliser, and in the manufacture of gunpowder.

Quoted by Richard Woodman in More Days, More Dollars, volume 4 of his brilliant and comprehensive history of the British Merchant Navy.

The Witwatersrand, also known as the 'Rand', is the richest gold reef in the world and gives its name to the South African currency.