Education of the best and highest kind

The vision of Alderman Henry Curry Wood

My mother was a teacher, a fact that I took completely for granted – in the 1950s and 1960s it was pretty much the only job thought suitable for a married woman with children, because she could be at home during the school holidays. It’s only recently that I’ve come to understand how unusual she was, and the importance of education to her family. When I went to university in 1969, I was one of only about 6% of school leavers who did so. In my mother’s day, it was more like 2-3% and just a quarter of those were women (although the ratio of men to women would change because of the war). A vanishingly small number would have been the granddaugher, as my mother was, of coal miners.

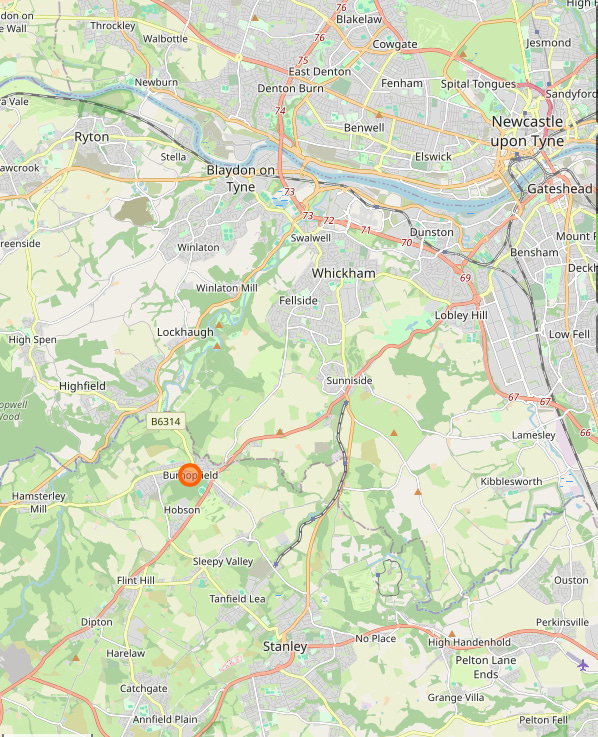

Doreen Wood was born in Throckley, a mining village on the western edge of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, in April 1921. She attended the local elementary school, where I know she was a star pupil thanks to the books on my shelves that bear inscriptions identifying them as school prizes: children’s classics like What Katy Did at School and Westward Ho! In 1931, when she was only ten, she moved up to the local secondary school in Lemington, where she showed ‘exceptional promise’, achieving her School Certificate after only four years. She went on to take her Higher Certificate in Maths, Physics, Chemistry, and Botany in 1938, at the age of seventeen. I haven’t found the relevant statistic but I suspect that, given the official school leaving age of fourteen, very few girls stayed on to take any examinations at all and even fewer specialised in sciences. She took up a place to study Maths at university, living at home and travelling daily to the newly created King’s College in Newcastle, which was at that time part of the federal University of Durham. In 1941 she graduated and took an abbreviated teaching diploma (an innovation because of the war), leaving in April 1942, as soon as she turned 21, for her assigned war work. As a mathematician she was sent to the radio department of the Royal Aircraft Establishment in Farnborough, Hampshire. She never talked about her work there (and had presumably had to sign the Official Secrets Act) but I remember her saying once that her colleagues were very surprised to find the new member of the team was a woman. It was there that she met my father, and I’ll write more about the RAE another time. A reference from my mother’s university tutor in 1947 describes her in these words: ‘Her war service has developed her into the reliable and yet somewhat original type of person we expected her to become’.

My mother never knew her grandfather on her father’s side, who had died four years before she was born, but I’m sure he would have been delighted by her academic success. Like her other grandfather, George Valentine Makepeace (who I wrote about here), Henry Curry Wood came from a mining family, but unlike George Makepeace he did not go down the pit. The decision to apprentice him to the local grocer transformed his prospects but I have no idea who decided or why. Did Henry himself rebel against the tradition that a miner’s son followed his father underground, or did his father choose a different future for his second son? Perhaps he was a delicate child who was not thought strong enough for hard physical labour, or he could have been recognised as a lad of unusual intelligence who deserved a chance to better himself. I’m only guessing, as I’m so often tempted to do when faced with a family mystery.

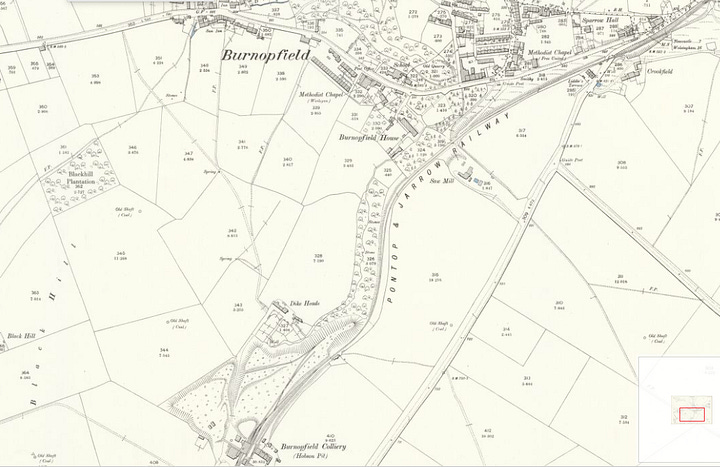

When Henry was born in 1853, the third of seven children, his father, Joseph Curry Wood, was a colliery banksman (like George Makepeace, in charge of signals and cage loading at the top of the shaft) at the Burnopfield colliery, also known as the Hobson Pit, a mine that had opened in 1742 and employed some 300 men. Joseph had already allowed his oldest son, William, to train as a house carpenter. Again, I can only speculate about his reasons, but wonder if it was associated with his change of name. At some point between the census of 1861 and that of 1871, the man known as Joseph Curry became Joseph Curry Wood. My reading of Victorian novels leads me to imagine he did this for financial reasons, that he stood to benefit from an inheritance or some other windfall, but I have so far found no evidence for this agreeable fantasy. I wonder if any more expert genealogists can suggest a better explanation? Whatever the reason, Jospeh must have been in a position to pay for his two older sons to be apprenticed instead of requiring them to contribute wages to the household, and yet his younger sons all followed him down the mine. In the census of 1881, Joseph the younger, aged 24, is a colliery engineman, and Thomas, 18, is a fireman.1 Even 15 year old Walton is working as a screener, picking the dirt from the coal. William the carpenter is also still living at home, but Henry, aged 26, has married and left home. He gives his occupation as grocer and he already has two children.

Ten years later, in 1891, Henry is the manager of the Cooperative store and living on the premises. Cooperative stores, which may be unfamiliar to readers outside the UK, were set up across the industrial north of England following the model of the men known as the Rochdale Pioneers. In 1844, at a time when living conditions were harsh and shopkeepers known to water down and adulterate their produce to increase profits, a group of 28 working men set up their own shop with the aim of providing food of decent quality at a fair price. Coops are still going strong today and I’m a member of my local one; I even have my phone contract with them. After the Burnopfield Coop opened in 1889 the village became a shopping centre for the surrounding colliery villages.

It is at this point that Henry Curry Wood becomes a public figure who can be traced through the newspaper archive. Following the Local Government Acts of 1888 and 1894, a system of local councils was being set up and Henry was elected to the first Tanfield Urban District Council, which would have covered an area including Burnopfield. By 1895 he was its chairman, and in 1892 he also stood for election to Durham County Council, representing the Tanfield Division. Henry was also a magistrate and a member of the Lanchester Board of Guardians, the body responsible overseeing the local workhouse - he was made Chairman of that as well! And yes, there was still a workhouse in Lanchester in 1895. A broadly complimentary report noted that the toilets were of the earth closet type and ‘generally appeared to lack the necessary supply of earth needed to deodorise their contents’. In 1904-5 Henry would have overseen the building of new children’s homes:

The new cottage homes for children which the Lanchester Board of Guardians have erected on a site adjacent to their workhouse, and facing the main street in the village of Lanchester, were opened on Friday. The new homes, which have been designated "Lee Hill" Cottages, have cost about £4,000, and the present accommodation is for 60 boys and girls. The scheme is for six cottages, four having been erected. The accommodation on the ground floor is sitting-room for the children, kitchen with scullery and larder, lavatory and bath, and stores.

(The Builder March 1905)

Politically Henry was said to be ‘a Liberal of the advanced school’, which I imagine implies a leaning towards socialism, and in 1914 was even seen as a potential candidate to succeed the outgoing Liberal MP for North West Durham. I have never been tempted to go into politics but I seem to have inherited a sense of public duty that has led me to undertake various kinds of voluntary work, including being a charity trustee. In that capacity I enjoyed discovering my great-grandfather’s antipathy towards red tape:

Red Tapeism

Alderman Henry Curry Wood was always known to be a Radical, although some critics of his principles now that he has attained such a high position of worth have now and again hinted that with his rise in the world he has lost touch with the interests of the working classes. We were therefore glad to hear that he protested at the last meeting of the Board of Guardians, of which he is the honoured Chairman at Lanchester, against the introduction of so much red tapeism.

(Consett Guardian 15 December 1916)

The title Alderman sent me down another rabbit hole, trying to unravel the difference between a councillor and an alderman. I’m sure someone will correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe aldermen were elected by their fellow councillors rather than the public at large, and had a senior status within the council.

But it was in the field of education that Henry Curry Wood made his greatest mark, and this is where the public record intersects with the personal. In addition to the lavish amounts of silver inherited from my Scottish great-grandparents, I acquired a couple of silver keys, inscribed with the names of schools, dates, and the name Alderman H. C. Wood. My great-grandfather presided over a huge programme of school building and was often presented with a commemorative key as part of the opening ceremony.

Henry himself was born at a time when elementary schooling was not compulsory and education for the working classes had been largely left to the church, with National schools set up by the Church of England and British schools by the Nonconformists.2 The Curry Wood family is said to have attended Hobson school, which may possibly have been attached to the colliery – the map shows it situated close by. By the time the Elementary Education Act was passed in 1870, Henry had already left school to become a grocer’s apprentice. The Act still did not make schooling compulsory but it did increase provision by establishing school boards, to be made up of elected members, who would set up and run schools for children aged 5-13 in areas where there was a shortage, to be funded out of the local rates. A further Act in 1880 made elementary schooling compulsory and in 1891, in the face of opposition from the Church of England, which didn’t want to lose the income from school fees, it was made free. The classes were extremely large by today’s standards and teachers relied on older pupils acting as monitors to assist them in delivering their lessons, but at least working class children were finally being given consistent access to learning. 2,500 boards were created between 1870 and 1896, and Henry became the first Chairman of the Tanfield School Board, said to be ‘one of the most progressive school boards in the county’.

School boards met with hostility in some quarters, especially when they took it upon themselves to expand the curriculum, fund higher elementary education for promising pupils, thus treading on the toes of the middle class grammar schools, and even set up evening classes for adults. (I expect Henry’s ‘progressive’ board was one of the culprits.) During the final ten years of the nineteenth century various attempts were made to abolish the boards, and in 1902 education was handed over to the new county councils, which were designated as education authorities. Henry Curry Wood was the obvious candidate to become Chairman of the Durham County Education Committee. In that capacity, he was responsible for an ambitious building programme, saying that during the years when school boards were ‘under notice to quit’ no work had been done and there were now arrears to make up. He was, according to his obituary, criticised on many occasions for his apparently profligate spending, but defended it as a capital investment that would pay dividends in future years when the impact of improved education was seen in the workforce.

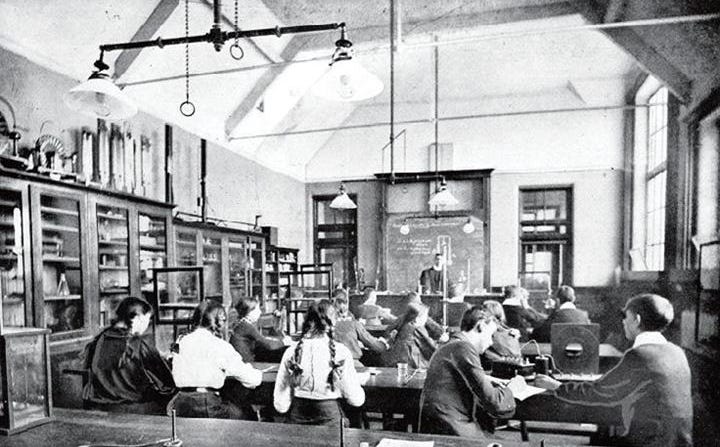

In a full page article in the Consett Guardian on Christmas Day 1908, about the opening of new schools in Consett and Blackhills, Henry’s speech is quoted. (On this occasion he was given a gold key but that one must have ended up with another of his descendants.) He talks of the council completing 20 schools, with another 34 being built and a further 30 approved. In total, some 50,000 school places were provided over four years at a cost of £680,000. His passion comes across as he speaks of enabling ‘the spread of education of the best and highest kind […] so that the child of the workman might rise to the highest places in the State’. This is not a view that everyone would have shared, with many of the upper and middle classes preferring the children of the working class to be educated to a limited level appropriate to their status. He goes on to say that he wishes ‘to produce the best results educationally while keeping effective control over the expenditure, always putting education first and expenditure second’. And although the news is all about the building, Alderman Wood is clear about the importance of good teaching, saying that ‘if he had to choose between bad buildings and a bad staff he would rather have the former than the latter’.

The Blackhill school provided accommodation for 250 infants and was described in some detail by the architect:

In Consett, the new schools could accommodate 1120 children:

The school that Henry Wood opened on 16th October 1912, the new Higher Elementary School and Pupil Teachers’ Centre at Tanfield Lea, had a special significance, since in 1919, at around the time that it was made into a grammar school, it was renamed the Alderman Wood School. It is now Tanfield School, but Alderman Wood is still remembered and I was touched to be contacted in 2012 by a former pupil and teacher who was involved in organising the school’s centenary celebration, and was compiling a biography of my great-grandfather, which can be read on the website of the Tanfield Association. The prospectus for 1914 is also available to read on the website. The emphasis on parental commitment is a sign of how few parents could afford for their children to delay earning until they were fifteen.

Object of the School

The primary object of this school is to provide education between the ages of 12 and 15 years for children who, having previously attended an ordinary public elementary school, give sufficient promise of being able to take up an extended curriculum of such a character as is here provided, and whose parents intend them to remain until they are at least 15 years of age.

In 1902 a magnificent new house was built for the manager of the Cooperative store. Woodlands is located on Sheephill in Burnopfield, where John Wesley had preached in a garden in 1746. Henry would probably have been pleased by the connection, since he was, in addition to all his other public positions, a renowned preacher. According to his obituary, Henry was a member of the Primitive Methodist Church and showed such precocious talent that from the age of 17 he was accepted as a preacher and encouraged to join the ministry. Primitive Methodism (now merged with the other Methodist churches) was a working class movement that began in the Pottery towns of the Midlands at the beginning of the nineteenth century and spread to the mining villages and factory towns of the north. Also known as Ranters, because of their enthusiastic style of preaching, Primitive Methodists wanted to return to what they saw as John Wesley’s original, purer form of Methodism. They encouraged education and self-improvement, and encouraged women to preach. A desire for social justice led many of them to become involved in politics and active in the trade union movement. Henry completed a course at the Primitive Methodist Theological Institute in Sunderland and was assigned to a preaching circuit, but after a year he gave it up and went back to selling groceries. It’s another of those mysteries that frustrate researchers in family history, since he clearly hadn’t lost his faith and was much in demand as a preacher in Burnopfield and other churches.

As a fan of the TV programme Location, Location, Location, there is nothing I like better than nosing around other people’s houses. Thanks to the comprehensive coverage of the Rightmove website, I was able to inspect Woodlands as it was the last time it was sold, in 2017. Surrounded by nearly an acre of wooded garden, it is an imposing stone-built three storey detached house with six bedroom, providing plenty of space for Henry, his wife Elizabeth and their six children. By the time of the 1901 census, the eldest daughter Ethel is already a school teacher (could she have made any other choice?) while the oldest son George is a college student, destined to become in later life a headmaster. The second daughter, Henrietta, was also to train as a teacher, while Arthur became an architect. My grandfather Wilfred, the third son, started work as a clerk at the Cooperative store, and I imagine his father hoped this would provide the same pathway to success that he had followed himself, but I’ll save Wilfred’s story for another post.

In an appreciation published in the Consett Guardian in December 2023, Henry is remembered as one of :

Two outstanding figures in the history of Burnopfield [who will be] handed down to the coming generations with a deep sense of the feeling of gratitude for their example, their labours on behalf of the village, and they outstanding personalities.

He is characterised as ‘stern, brusque, autocratic, scholarly, a visionary and a dreamer’. But if that makes him sound too severe, he was also a keen cricketer. According to his obituary, in his younger days, playing for the Burnopfield team, he was a good solid bat ‘with a view to breaking the bowling’, and when he became too old to play he turned umpire. All three of his sons joined the team, which performed well against visiting sides.

Henry’s wife, Elizabeth, died in 1904, only two years after the new house was built and without seeing the success of her husband’s school building programme, but after allowing a respectable year to elapse, he remarried. His new wife, Emma Errington, was some fourteen years his junior and had been a clerk at the Cooperative store. She took on the role of stepmother to the two youngest girls, who were only 11 and 14 when their mother died, and my grandfather Wilfred, who was 17. After Henry retired, which must have been around the time of the outbreak of World War I, he and Emma moved to a house named Lakeside in Saltwell View, Gateshead, overlooking Saltwell Park, and presumably its lake. But when Wilfred joined the army, Henry took on the management of his son’s grocery business in Meadowfield, Durham.

In April 1916, Henry had been elected Vice Chairman of Durham County Council, and in January 1917, in his capacity as Chair of the Education Committee, he agreed to meet with a group of teachers to discuss the problem of war bonuses. These were additional payments to help with living costs and had been much criticised, with some teachers even returning the bonus paid to them. Everyone believed that Henry was the man who would come up with a solution. Sadly, however, on the morning of Monday 5th February, Henry and Emma set off to catch the 7.43 train to Durham, on their way to manage Wilfred’s shop, but on arriving at Gateshead Station, Henry suffered a catastrophic heart attack. He was carried into the waiting room and a doctor was sent for, but it was too late.

Henry Wood’s funeral service was attended by a large number of MPs, councillors and aldermen, while the chief constable was represented by an inspector accompanied by a ‘posse’ of policemen. Half a dozen clergymen took part in the service and six Co-op employees were pallbearers when he was buried in St James' Churchyard, Burnopfield. His unexpected death left his financial affairs in a tangle. He had been investing in property with mortgages, and it was not until 1956 that a deed of family agreement eventually sorted out what was due to his various children and their descendants. I suppose it only goes to show that, like many of us, he was a better custodian of public money than of his own. Although the school no longer bears his name, Alderman Henry Curry Wood lives on in the name of a road on an industrial estate in Tanfield Lea.

It proved surprisingly hard to pin down exactly what this job involved, but the role seems to have originally been to ensure the safety of the men by going down first and testing for dangerous gas. It later evolved into the job known as Deputy: ‘The deputies go to work two hours before the hewers. Each deputy, during the absence of the back-overman, is responsible for the management of the district of the pit over which he is appointed. Their work also includes that of supporting the roof with props or wood, removing props from old workings, changing the air currents when necessary, and clearing away any sudden eruption of gas or fall of stone that might impede the work of the hewer, or in delegating these duties to others.’ (Source: Durham Mining Museum: Mining Occupations)

My understanding of the education system is mainly drawn from the work of Derek Gillard, which he has generously made available online (Gillard D (2018) Education in the UK: a history www.education-uk.org/history)

I really enjoyed learning this history. We so desperately need civic minded men like Henry today, especially here in the US where both local and federal government are busy gutting public education.

A great piece thank you.