Hello and welcome to my new subscribers. I was delighted by the response to my post about my Scottish grandmother. After just a couple of weeks on Substack, and still finding my way around, it was very encouraging to read your comments, so thank you, and do keep giving me your feedback. This post is an extended version of a story that will appear in my new book.

We have become much more aware in recent years that any history of Britain is incomplete if we ignore the presence of Black people. Historians like David Olusoga and Miranda Kaufman have challenged us all to recognise the importance of Black British history, but I was still taken by surprise when I found a reference in one of my grandmother’s fragments of memoir to a Black friend of her father’s.

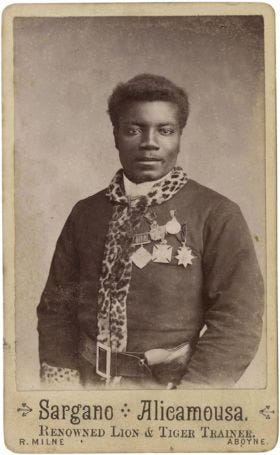

‘In morocco-covered album with ornate brass clasps that lay on a drawing room table was one photograph which I greatly admired. It was a cabinet sized likeness of Sargano, a foreigner and lion tamer. He was arrayed in tight trousers, high laced boots and a striking leopard skin tunic. He was of powerful build with fine eyes and a resolute expression. He was a friend of my father’s from Aboyne days and we were told that there was no braver man.’

My grandmother identified him as a foreigner but did not think to mention his colour; it was more important that he was her father’s friend. But an online search produced an image of a man who appears to be of Black African or Caribbean descent. Like the photograph my grandmother remembered, this picture of Sargano Alicamousa is cabinet sized, a popular format from the 1860s through to World War I. Measuring about 6.5 by 4.25 inches, it is mounted on thick card and has the photographer’s details printed on the front. In this case the portrait is credited to R. Milne, Aboyne. Sargano was in distinguished company. Robert Milne, a well-known photographer who had studios in the villages of Ballater and Aboyne on Deeside, near Balmoral, received a royal warrant in 1896. The National Portrait Gallery has examples of his portraits of Queen Victoria, and members of her family and household, including her ghillie John Brown and Hafiz Abdul Karim, known as the Munshi.

Victorian circuses were diverse communities, with performers and other workers from a range of countries and ethnic backgrounds. An article in the Journal of Victorian Culture Online describes how the proprietors liked their lion tamers, in particular, to be suitably African in appearance. One of the best known was Martini Maccomo, known as the Lion King, who may have come been born in Angola but was quite possibly from the West Indies. Sargano Alicamousa was the stage name taken by another lion tamer from the Caribbean, whose real name was John Humphreys (although, confusingly, he was not the first to use the name). Having identified him, I needed to find out when he might have met my great-grandfather, George Henderson Smythe.

George left school aged twelve to become a gardener’s boy and worked his way up to become head gardener to the Marquis of Huntly, whose home was Aboyne Castle on Royal Deeside. He too was photographed by Robert Milne, a mark of his enhanced social status. The gardener’s cottage in Aboyne was where my grandmother Jean was born in 1886, but four years later the family moved away, so I deduced that her father must have met Sargano in the 1880s.

I can easily spend days immersed in the nineteenth century newspaper archives. I like to see what else was happening in the wider world at the time of the particular event I’m interested in, and the small ads are endlessly fascinating. When I set myself the task of establishing when Sargano was in Aboyne, I found a wealth of material. In August 1884 Bostock’s Grand Star Menagerie made its first tour of Aberdeenshire, with one of the star attractions being Sargano, ‘the Renowned African Lion Hunter, who will at each representation perform his Deeds of Daring, in a manner that cannot fail to elicit the admiration of all beholders.’ (I will admit here that I am a big fan of Dramatic Victorian Capital Letters.) I can find no mention of Bostock’s visiting Aboyne on this occasion, but in June 1886 the show returned to Scotland, with a collection of animals that included ‘Peruvian Giraffes, strange and stately animals’ - presumably llamas - and ‘Carnivora’ ‘Headed by Wallace, the most Symmetrical Lion in Europe’ - and no, I have no idea why his symmetry should be so prized. That year Bostock’s was due to be in Aboyne on 22 June. It was later in this tour that an ‘exciting incident’ took place in Monymusk. Sargano entered the cage of the two young lions, ‘when the male one sprang upon him and seized him with his teeth in the right arm below the shoulder’. Fortunately Mr Bostock rushed to the rescue and Sargano was able to remain in the cage and subdue the animal, escaping with bite marks and scratches.

In March 1887 Sargano left Bostock’s and set up a menagerie of his own. Interviewed on a visit to Dundee, he explained that he had bought four lions for £100 each and toured Scotland with them. It’s not straightforward to compare sums of money across time, but £100 would have been close to the annual wage of some workers, so Sargano must have been paid well. Amongst the tricks he taught his animals was to play dead while he lay down between them. He also taught one of them to fire a pistol - a feat that I find rather hard to visualise. In June 1888 Sargano placed an advertisement in the Aberdeen Evening Press ‘received too late for classification’, that appeared alongside assorted requests for lodgings, job offers, the loss of two bushels of corn, an appeal for the return of a silver mounted staff taken in error, and a plea for the Party who sent Anonymous letter to kindly forward his Address. It read: ‘All should see the daring feats of Sargano, the King of all Lion Tamers. Worth one hundred miles journey to see. Admission 6d.’ But perhaps his delayed advertising brought him reduced audiences because the following year, 1889, he was back with Bostock’s and visiting Aboyne on 29 May.

I concluded that George Smythe and Sargano could easily have met on more than one occasion, perhaps even annually for a few years. I am obscurely pleased to know that my great-grandfather admired and made a friend of a man who would have been shunned by many at the time for the colour of his skin. On the face of it the two men had little in common. George had never left rural Aberdeenshire, although he was clearly ambitious, winning prizes for his vegetables and standing for election to the school board and the town council. Sargano’s life story was a great deal more dramatic.

In September 1886 a feature headed ‘The Career of a Roving Lion Tamer’ occupied a column and a half in the Aberdeen Weekly News, vying for attention with the political crisis surrounding the abdication of Prince Alexander of Bulgaria, an account of the eviction of tenant farmers in Killarney, and a shocking murder in Paris. The journalist who interviewed Sargano described him as ‘a good-looking Indian’, further adding to the confusion about his origins, and wrote admiringly of his ‘soft brown eyes and sweeping dark eyelashes [that] betokened an irresistible gentility of spirit’. He wore a greenish blue tunic and ‘his bosom was bedecked with a constellation of medals’, awarded by his admirers. Sargano explained that he had been born in 1859 on St Vincent, one of the Windward Islands, the son of an farmer who was, I imagine, a descendant of slaves (slavery was only abolished in 1834). He was an adventurous boy, skipping school to go down to the harbour and talk to the sailors. At the age of thirteen he accepted an offer to serve an English naval officer and left home, never to return. They travelled to Africa, where Sargano encountered his first lion, but then his master resigned his commission and settled back in England, where he tried to turn Sargano into a house servant like Dr Johnson’s Francis Barber. Sargano informed the journalist proudly that he preferred the risk of starvation to a life of servitude. He ran away again, this time to London, where he found employment in Sanger’s circus.

His first job was to ride one of the elephants that promenaded around the stage, and then he was allowed to help the keepers feed the lions and tigers and clean out their dens. One day Mr Sanger dared him to enter the lions’ cage but when it was time for him to come out again, one of the beasts was lying in front of the door refusing to move. Sargano tapped him with a stick. The creature growled ferociously but allowed him to leave and from that day on Sargano Alicamousa was a lion tamer who travelled round Britain and Europe with the circus. When asked about his most dangerous moment, he recounted how Wallace (the symmetrical beast) attacked him in 1881 in Birmingham and he ended up in hospital. But he informed the journalist that he intended to live and die a lion tamer, declaring, ‘It is a noble work because none but a hero can do it.’

I love family history and newspaper archives as well, I couldn't have written my books without Ancestry and the BNA.. or they would certainly have been more boring! Also, wasn't Wallace the name of the lion in Albert and the Lion? It always seemed an unlikely name for a beast, but it had history, it seems!

That is a fascinating story. I can imagine the wonder in rural Aberdeenshire at the sights, sounds and smells of the circus.

In my home village of Rothes we also have a Black African connection in the person of "Byway", who was adopted in Africa as a child by Major Grant of Glen Grant distillery and brought back to be a footman/butler. As a child I remember him clearly. He always wore a suit and tie, with a V-neck pullover. My father remembered him as a talented footballer for the local football team, and for his choice of beverage if offered a drink in a local pub- "I'll have a gin please". This despite his distillery upbringing and in a village where whisky was THE drink. He is buried in the village cemetery, where people still tend his grave. https://www.northern-scot.co.uk/news/the-rhodesian-rothesian-the-unique-story-of-biawa-makalaga-296917/