Another Song at Sunset

Jean Baxter, Scots poet and friend of Lewis Grassic Gibbon

I’m delighted to announce the publication of my new book Another Song at Sunset in both paperback and kindle editions. So what’s it about? Perhaps the best way to explain is to quote from the Foreword:

Every copy of Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Sunset Song carries a dedication to my grandmother, Jean Baxter. On the title page of my own first edition the author has added a personal message in his distinctive, elegant handwriting: ‘For Jean Baxter in complement to the dedication’. Grassic Gibbon was the pen name chosen by James Leslie Mitchell when he wrote his most famous novel, the first in a trilogy known as A Scots Quair. It tells the story of Chris Guthrie, who was born into a crofting family in the north east of Scotland at the end of the nineteenth century. Torn between her love of the land and her desire for education, Chris has for many readers come to symbolise Scotland itself. She has much in common with Leslie Mitchell himself and his wife Ray, but she is also based in part on my grandmother, who was his friend.

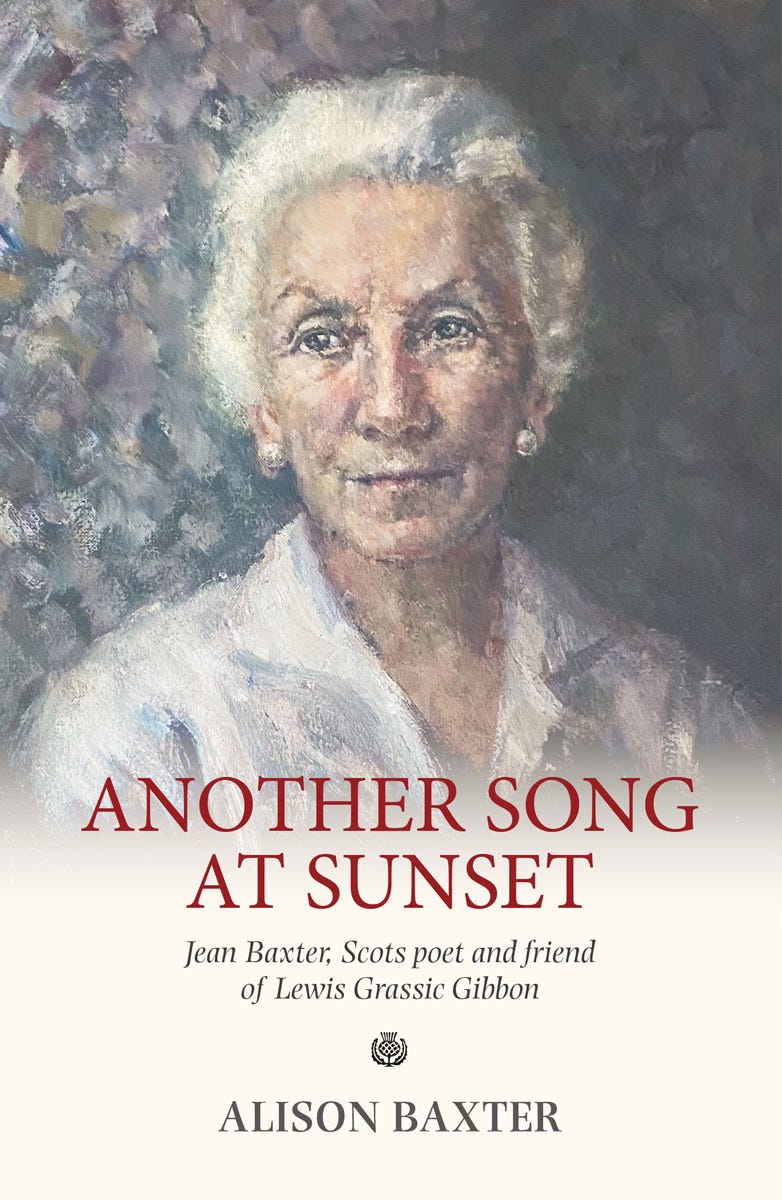

As a child growing up in England I knew little about my grandmother’s Scottish past. My father’s mother was simply ‘Little Gran’, so called to distinguish her from ‘Big Gran’, my mother’s mother – who was not particularly large either, but inappropriate family nicknames have a habit of sticking. Big Gran was a Geordie who called me ‘pet’ whilst Little Gran spoke with an educated Scottish accent reminiscent of another Jean, Muriel Spark’s fictional Miss Brodie. There was a hint of the Mediterranean in her looks although she knew of nothing in her heritage to account for this. She was once asked to model for an oil painting of an imaginary Spanish lady. With her white hair plaited in a coronet under a black lace mantilla she made a most convincing señora from Seville. A second portrait, without the mantilla, a gift from the artist to the sitter, now watches over me from my dining room wall and is reproduced on the cover of this book.

When we visited Gran in her flat in Wokingham, she used to talk about two friends with confusingly gender neutral names: Ray, who was a woman, and Leslie, who was a man, and dead. Eventually I learned that these were the novelist Lewis Grassic Gibbon, born James Leslie Mitchell, and his wife Rebecca Middleton, known as Ray. Leslie Mitchell died just before his thirty-fourth birthday in 1935 and even after thirty years, his loss was an enduring sorrow.

It’s a project that I began some ten years ago and then put aside because I couldn’t decide how best to tackle it. Was it a book about my gran, or about Grassic Gibbon? Publishers and agents wanted Grassic Gibbon. I wasn’t sure that I did, although as I got further into my research I realised that there were aspects of his life that had not been fully explored by previous biographers, writing at a more reticent time. But I was still reluctant to embark on a full scale biography of the famous novelist, and it turned out that I was right. I’ve recently been privileged to read, in manuscript form, a book that will surely be recognised as the definitive version of the life and work of James Leslie Mitchell when it’s published.

Once I’d decided to focus on my gran, I asked myself if I should fictionalise parts of her story, as I had done with my previous book, A Cornish Cargo. But then I would risk comparison with Sunset Song itself, and I knew I couldn’t compete with Scotland’s favourite novel. Also, I had chunks of my gran’s own writing that I wanted to use. She was a good enough writer to merit being quoted directly rather than paraphrased, and that would give me the variation in style that I’d achieved by using fictionalised episodes about my Cornish ancestors. The disadvantage was that the material is uneven in its coverage. There’s a lengthy account of gran’s friendship with Grassic Gibbon, a detailed account of her schooldays in the 1890s, and various scribbled pages about her early childhood, which give a fascinating insight into the social history of Scotland. But that left big gaps that I had to fill with my own research, and there are important periods of her life, including 1914-18, where I drew almost a complete blank.

It was only after I’d produced several drafts that a Scottish acquaintance recommended including gran’s own poetry. I suddenly realised that of course that was the best way of letting her speak for herself. The poems are not (with one exception) deeply personal, but they are autobiographical in the sense that she was writing, in exile in England, about the rural Scotland of her childhood. It is the world of Sunset Song seen through different eyes. Republishing the poems meant getting to grips with gran’s native language, the Doric of north-east Scotland, frustratingly similar to English but still a foreign tongue. But it was an effort that paid off. The more I worked on the transcriptions, the more I felt I was getting to know my gran, and I hope readers will feel the same.

Oh I’ve just found this to read.

That's fascinating Alison. I look forward to reading it